MIAMI — Hudson Dunn has always been an active boy.

His daycare teachers called him “demanding” and “independent.” In preschool, he preferred singing and daydreaming to learning the ABCs. By the time he was in kindergarten in Broward County, Hudson was banned from class field trips unless his mother came along to keep track of him. He often came home crying.

“It created an environment in the classroom where he was labeled a bad kid,” said his mom, Jenine Dunn.

Hudson has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, or ADHD — one of the most commonly diagnosed mental health disorders in children. The Centers for Disease Control estimates 11 percent of American kids have ADHD.

The list of symptoms for kids who have ADHD reads like a recipe for problems in school: trouble paying attention and completing tasks. Being fidgety, talkative and impulsive. Difficulty following rules, making friends and keeping track of things — like homework or class materials.

Increasing academic demands have only made it harder for kids with ADHD, argues Dr. Jeffrey Brosco, professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. With kids spending more time preparing for standardized tests and less time playing at recess, Brosco says the rate of ADHD in children has doubled since the 1970s.

“We’ve increased the academic demands, but we’ve also reduced our demands for allowing children to figure out how to spend their time,” Brosco said. “Young children learn best by play and by creative kinds of pursuits, and not just practice with reading, writing and arithmetic.”

Take, for example, the amount of time that kids spend doing homework.

In a paper published in February in JAMA Pediatrics, Brosco and co-author Anna Bona point out that elementary-aged kids in 1997 spent more than two hours on homework, compared with kids in the 1980s who spent less than an hour.

Dunn said the academic rigor of kindergarten definitely contributed to the difficulties her son, Hudson, faced in school. Whereas she remembers hatching eggs and making maple syrup in kindergarten, Dunn’s son was expected to fill out worksheets and write book reports.

“There’s very little free time for imagination. They want these kids in kindergarten sitting at a desk for seven hours a day,” she said. “It creates an incredible amount of stress.”

There could be other causes for increasing ADHD rates. Dr. William Pelham is a world-renowned ADHD researcher at Florida International University. He credits two major developments with boosting the number of diagnoses: One, recognition by the federal government in 1991 that children with ADHD are entitled to special education services in school. Second, the development and marketing of new pharmaceutical drugs in the 2000s.

Whatever the cause, Pelham has focused on effective treatments over his decades-long career. Every summer, Pelham, who leads FIU’s Center for Children and Families, runs a summer camp for children with ADHD at Paul W. Bell Middle near Sweetwater, Fla.

There are all the activities you’d expect from a summer camp, like basketball and silly songs. But there’s also a classroom component with a heavy dose of behavior therapy, where there’s a consequence for every action — good or bad.

The therapy is on display in Herbert McArthur, Jr.’s class. During the school year, he’s a Miami-Dade high school teacher. In the summertime, he teaches a roomful of younger students who have ADHD.

He weaves between their desks, offering nonstop praise.

“I like the way you’re raising your hand without calling out,” he tells one.

“Thank you for using your materials appropriately,” he says to another.

It comes every 30 seconds or so, a pleasant reminder for every tiny thing done right. Because for McArthur’s students, every moment spent sitting in class and following the rules is a monumental achievement.

Implementing behavior modification strategies in the classroom takes time — time that teachers don’t often feel like they have. A recent survey by the American Federation of Teachers found that being pressed for time was a leading cause of stress among teachers.

Every moment spent fixing bad behavior, praising good behavior or redirecting a student to the task at hand is a moment of teaching that is lost.

“The bell-to-bell instruction, it doesn’t allow for the extra pat on the back,” said McArthur, the summer camp teacher. “You’re looking at the clock.”

Pelham and his team focus on behavior modification because, he says, it works. Combined with parent training, Pelham has found that starting with behavior-based treatment rather than medication is more effective and costs less. His findings, released in February, led the CDC to change the recommended course of treatment for children with ADHD.

Still, children in Florida are far more likely to receive medicine over therapy. In a 2010 CDC survey, more than 70 percent of kids had taken medication in the past week, while only half had received behavior therapy in the past year.

“The problem is that there is no pharmaceutical company for better classroom management practices. There is no pharmaceutical company for better parenting programs. So you don’t have gigantic industries helping parents and helping teachers,” Pelham said.

Ava Goldman, a director for Miami-Dade’s Exceptional Student Education, said the school district works with Pelham to train teachers to work with students who have ADHD. The district and Pelham also recently collaborated to revamp the accepted classroom accommodations students with ADHD can receive.

Article about writing pdf documents

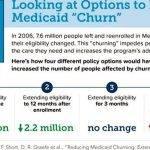

Article about writing pdf documents Writing journal articles requirements for medicaid

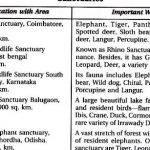

Writing journal articles requirements for medicaid Article writing on save wildlife photos

Article writing on save wildlife photos Writing articles for websites for money

Writing articles for websites for money Article 2 the executive branch summary writing

Article 2 the executive branch summary writing