A paragraph is a number of sentences which are organized and coherent, and therefore are all related one subject. Nearly every written piece you accomplish that is more than a couple of sentences ought to be organized into sentences. It is because sentences show a readers in which the subdivisions of the essay begin and finish, and therefore assist the readers begin to see the organization from the essay and grasp its primary points.

Sentences can contain many different types of knowledge. A paragraph could contain a number of brief examples or perhaps a single lengthy instance of an over-all point. It could describe a location, character, or process narrate a number of occasions compare or contrast several things classify products into groups or describe causes and effects. Whatever the type of information they contain, all sentences share certain characteristics. Probably the most important could well be a subject sentence.

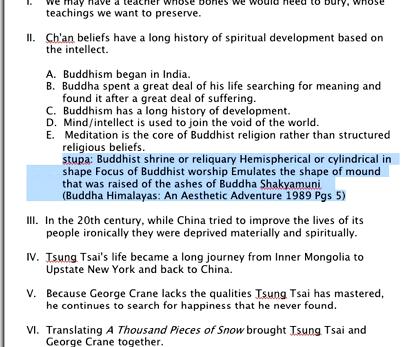

Subject SENTENCES

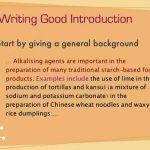

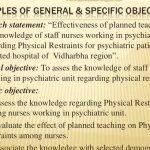

A properly-organized paragraph supports or develops just one controlling idea, that is expressed inside a sentence known as the subject sentence. A subject sentence has lots of important functions: it substantiates or supports an essay’s thesis statement it unifies the information of the paragraph and directs an order from the sentences also it advises the readers from the susceptible to be discussed and just how the paragraph will talk about it. Readers generally go looking towards the first couple of sentences inside a paragraph to look for the subject and outlook during the paragraph. That’s why it’s frequently better to place the subject sentence in the very start of the paragraph. In some instances, however, it’s more efficient to put another sentence prior to the subject sentence—for example, a sentence linking the present paragraph towards the previous one, a treadmill supplying history.

Although most sentences must have a subject sentence, there’s a couple of situations whenever a paragraph may not require a subject sentence. For instance, you could possibly omit a subject sentence inside a paragraph that narrates a number of occasions, if your paragraph continues developing a concept that you simply introduced (having a subject sentence) in the last paragraph, or maybe all of the sentences and details inside a paragraph clearly refer—perhaps not directly—to a primary point. Most your sentences, however, must have a subject sentence.

PARAGRAPH STRUCTURE

Most sentences within an essay possess a three-part structure—introduction, body, and conclusion. You can observe this structure in sentences whether or not they are narrating, describing, evaluating, contrasting, or analyzing information. Each area of the paragraph plays a huge role in communicating your intending to your readers.

Introduction. the very first portion of a paragraph will include the subject sentence and then any other sentences at the outset of the paragraph that provide history or give a transition.

Body. follows the introduction discusses the controlling idea, using details, arguments, analysis, examples, along with other information.

Conclusion. the ultimate section summarizes the connections between your information discussed in your body from the paragraph and also the paragraph’s controlling idea.

The next paragraph illustrates this pattern of organization.

Within this paragraph the subject sentence and concluding sentence (CAPITALIZED) both assist the readers keep your paragraph’s primary reason for mind.

SCIENTISTS Began To SUPPLEMENT A Feeling OF SIGHT In Several WAYS. While watching small pupil from the eye installed. on Mount Palomar, an excellent monocle 200 inches across, with it see 2000 occasions farther in to the depths of space. Or they appear via a small set of lenses arranged like a microscope into a small amount of water or bloodstream, and magnify up to 2000 diameters the living creatures there, a few of which are among man’s most harmful opponents. Or. to see distant happenings on the planet, they will use a few of the formerly wasted electromagnetic waves to hold television images that they re-create as light by whipping small crystals on the screen with electrons inside a vacuum. Or they are able to bring happenings of lengthy ago and away as colored movies, by organizing silver atoms and color-absorbing molecules to pressure light waves in to the patterns of original reality. Or to see into the middle of a steel casting or even the chest of the hurt child, they give the data on the beam of penetrating short-wave X sun rays, after which convert it back to images we are able to see on the screen or photograph. THUS Nearly Every Kind Of Radio Waves YET DISCOVERED Has Been Utilized To Increase OUR Feeling Of SIGHT In Some Manner.

George Harrison, “Faith and also the Researcher”

COHERENCE

Inside a coherent paragraph, each sentence relates clearly towards the subject sentence or controlling idea, but there’s more to coherence than this. If your paragraph is coherent, each sentence flows easily in to the next without apparent shifts or jumps. A coherent paragraph also highlights the ties between old information and new information to help make the structure of ideas or arguments obvious towards the readers.

Combined with the smooth flow of sentences, a paragraph’s coherence can also be associated with its length. For those who have written a really lengthy paragraph, one which fills a dual-spaced typed page, for instance, you can examine it carefully to find out if it ought to begin a new paragraph in which the original paragraph wanders from the controlling idea. However, if your paragraph is extremely short (just one or two sentences, possibly), you may want to develop its controlling idea more completely, or blend it with another paragraph.

Many other techniques which you can use to determine coherence in sentences are described below.

Repeat key phrases or words. Specifically in sentences that you define or identify an essential idea or theory, remain consistent in terms you make reference to it. This consistency and repetition will bind the paragraph together which help your readers understand your definition or description.

Create parallel structures. Parallel structures are produced by constructing several phrases or sentences that have a similar grammatical structure and employ exactly the same areas of speech. By creating parallel structures you are making your sentences clearer and simpler to see. Additionally, repeating a design in a number of consecutive sentences helps your readers begin to see the connections between ideas. Within the paragraph above about scientists and also the feeling of sight, several sentences in your body from the paragraph happen to be built inside a parallel way. The parallel structures (that have been emphasized ) assist the readers observe that the paragraph is organized as some types of an over-all statement.

Remain consistent in perspective, verb tense, and number. Consistency in perspective, verb tense, and number is really a subtle but essential requirement of coherence. Should you shift in the more personal you towards the impersonal “one,” from past to provide tense, or from “a man” to “they,” for instance, you are making your paragraph less coherent. Such inconsistencies may also confuse your readers making your argument harder to follow along with.

Use transition phrases or words between sentences and between sentences. Transitional expressions highlight the relationships between ideas, so that they help readers follow your train of thought or see connections they might otherwise miss or do not understand. The next paragraph shows how carefully selected transitions (CAPITALIZED) lead the readers easily in the summary of the final outcome from the paragraph.

I don’t desire to deny the flattened, minuscule mind from the large-bodied stegosaurus houses little brain from your subjective, top-heavy perspective, However I do desire to assert that people shouldn’t expect a lot of animal. To Begin With, large creatures have relatively smaller sized brains than related, small creatures. The correlation of brain size with bodily proportions among kindred creatures (all reptiles, all mammals, For Instance) is remarkably regular. Once we change from promising small to large creatures, from rodents to tigers or small lizards to Komodo dragons, brain size increases, Although not so quick as bodily proportions. Quite Simply, physiques grow quicker than brains, And enormous creatures have low ratios of brain weight to bodyweight. Actually, brains grow no more than two-thirds as quickly as physiques. Because we don’t have any need to think that large creatures are consistently stupider than their smaller sized relatives, we have to conclude that giant creatures require relatively less brain to complete in addition to smaller sized creatures. IF we don’t recognize this relationship, we will probably underestimate the mental power large creatures, dinosaurs particularly.

Stephen Jay Gould, “Were Dinosaurs Dumb?”

SOME Helpful TRANSITIONS

(modified from Diana Hacker, A Author’s Reference )

To exhibit addition: again, and, also, besides, essential, first (second, etc.), further, in addition, additionally, to begin with, furthermore, next, too To provide examples: for instance, for example, actually, particularly, that’s, as one example of To check: also, very much the same, likewise, similarly To contrast: although, but, simultaneously, but, despite, despite the fact that, however, in comparison, regardless of, nonetheless, on the other hand, however, still, though, yet In summary or conclude: overall, to conclude, quite simply, in a nutshell, in conclusion, overall, that’s, therefore, to summarize To exhibit time: after, afterward, as, as lengthy as, when, finally, before, during, earlier, finally, formerly, immediately, later, meanwhile, next, since, shortly, subsequently, then, after that, until, when, while To exhibit place or direction: above, below, beyond, close, elsewhere, farther on, here, nearby, opposite, left (north, etc.) To point logical relationship: accordingly, consequently, because, consequently, because of this, hence, if, otherwise, since, so, then, therefore, thus

Created by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana College, Bloomington, IN

wts/shtml_navs/iub.digital” />

Writing Tutorial Services

Center for Innovative Learning and teaching

Wells Library Learning Commons, 1320 E. Tenth St. Bloomington, IN 47405

Phone: (812) 855-6738

Comments

Subject sentences and signposts make an essay’s claims obvious to some readers. Good essays contain both. Subject sentences reveal the primary reason for a paragraph. They reveal the connection of every paragraph towards the essay’s thesis, telegraph the purpose of a paragraph, and inform your readers what to anticipate within the paragraph that follows. Subject sentences also establish their relevance immediately, making obvious why what exactly they are making are essential towards the essay’s primary ideas. They argue instead of report. Signposts. his or her name suggests, prepare the readers for something new within the argument’s direction. They reveal what lengths the essay’s argument has progressed vis–vis the claims from the thesis.

Subject sentences and signposts occupy a middle ground within the writing process. They’re neither the very first factor a author must address (thesis and also the broad strokes of the essay’s structure are) nor could they be the final (that’s by visiting to sentence-level editing and polishing). Subject sentences and signposts deliver an essay’s structure and intending to a readers, so that they are helpful diagnostic tools towards the writer—they tell you if your thesis is arguable—and essential guides towards the readers

Types of Subject Sentences

Sometimes subject sentences are really two or perhaps three sentences lengthy. When the first constitutes a claim, the 2nd might think about claiming, explaining it further. Consider these sentences as asking and answering two critical questions: So how exactly does the phenomenon you are discussing operate? How come it operate because it does?

There is no set formula for writing a subject sentence. Rather, you need to try to vary the shape your subject sentences take. Repeated too frequently, any method grows boring. Listed here are a couple of approaches.

Complex sentences. Subject sentences at the outset of a paragraph frequently match a transition in the previous paragraph. This can be made by writing a sentence which contains both subordinate and independent clauses, as with the instance below.

Although Youthful Lady having a Water Pitcher depicts a mystery, middle-class lady in an ordinary task, the look is much more than “realistic” the painter [Vermeer] has enforced their own order on there to bolster it.

This sentence employs a helpful principle of transitions: always change from old to new information. The subordinate clause (from “although” to “task”) recaps information from previous sentences the independent clauses (beginning with “the lookInch and “the painter”) introduce the brand new information—a claim about how exactly the look works (“greater than realistic'”) and why it really works because it does (Vermeer “strengthens” the look by “imposing order”).

Questions. Questions, sometimes in pairs, also make good subject sentences (and signposts). Think about the following: “Will the commitment of stability justify this constant hierarchy?” We might fairly think that the paragraph or section that follows will answer the issue. Questions are obviously a kind of inquiry, and therefore demand a solution. Good essays shoot for this forward momentum.

Bridge sentences. Like questions, “bridge sentences” (the word is John Trimble’s) make a great replacement for more formal subject sentences. Bridge sentences indicate both what came before and just what comes next (they “bridge” sentences) with no formal trappings of multiple clauses: “But there’s an idea for this puzzle.”

Pivots. Subject sentences don’t always appear at the outset of a paragraph. When they are available in the center, they indicate the paragraph can change direction, or “pivot.” This tactic is especially helpful for coping with counter-evidence: a paragraph begins conceding a place or stating a well known fact (“Psychiatrist Sharon Hymer uses the word narcissistic friendship’ to explain the first stage of the friendship such as the one between Celie and Shug”) after following on this initial statement with evidence, after that it reverses direction and establishes claims (“Yet. this narcissistic stage of Celie and Shug’s relationship is just a temporary one. Hymer herself concedes. “). The pivot always requires a signal, a thing like “but,” “yet,” or “however,” or perhaps a longer phrase or sentence that signifies an about-face. It frequently needs several sentence to create its point.

Signposts operate as subject sentences for whole sections within an essay. (In longer essays, sections frequently contain greater than a single paragraph.) They inform a readers the essay takes a submit its argument: delving right into a related subject like a counter-argument, walking up its claims having a complication, or pausing to provide essential historic or scholarly background. Simply because they reveal the architecture from the essay itself, signposts help remind readers of the items the essay’s stakes are: how it is about, and why it’s being written.

Signposting can be achieved inside a sentence or two at the outset of a paragraph or perhaps in whole sentences that provide as transitions between one area of the argument and subsequently. The next example originates from an essay analyzing the way a painting by Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of the Train, challenges Zola’s declarations about Impressionist art. A student author wonders whether Monet’s Impressionism can be as dedicated to staying away from “ideas” in support of direct sense impressions as Zola’s claims would appear to point out. This is actually the start of essay’s third section:

It’s apparent within this painting that Monet found his Gare Saint-Lazare motif fascinating at most fundamental degree of the play of sunshine along with the loftiest degree of social relevance. Arrival of the Train explores both extremes of expression. In the fundamental extreme, Monet satisfies the Impressionist purpose of recording the entire-spectrum results of light on the scene.

The author signposts this within the first sentence, reminding readers from the stakes from the essay itself using the synchronised references to sense impression (“play of sunshineInch) and intellectual content (“social relevance”). The 2nd sentence follows on this concept, as the third works as a subject sentence for that paragraph. The paragraph next commences with a subject sentence concerning the “cultural message” from the painting, something which the signposting sentence predicts by not just reminding readers from the essay’s stakes but additionally, and quite clearly, indicating exactly what the section itself contains.

2000, Elizabeth Abrams, for that Writing Center at Harvard College

Paulo lourenco phd thesis writing

Paulo lourenco phd thesis writing Literature review outline for thesis proposal

Literature review outline for thesis proposal Ucla english writing dept thesis tutor

Ucla english writing dept thesis tutor Writing your thesis introduction sample

Writing your thesis introduction sample Writing good research objectives for thesis

Writing good research objectives for thesis