Guidelines on writing a research proposal

by Matthew McGranaghan

This is a work in progress, intended to organize my thoughts on the process of formulating a proposal. If you have any thoughts on the contents, or on the notion of making this available to students, please share them with me. Thanks.

This is a guide to writing M.A. research proposals. The same principles apply to dissertation proposals and to proposals to most funding agencies. It includes a model outline, but advisor, committee and funding agency expectations vary and your proposal will be a variation on this basic theme. Use these guidelines as a point of departure for discussions with your advisor. They may serve as a straw-man against which to build your understanding both of your project and of proposal writing.

Proposal writing is important to your pursuit of a graduate degree. The proposal is, in effect, an intellectual scholastic (not legal) contract between you and your committee. It specifies what you will do, how you will do it, and how you will interpret the results. In specifying what will be done it also gives criteria for determining whether it is done. In approving the proposal, your committee gives their best judgment that the approach to the research is reasonable and likely to yield the anticipated results. They are implicitly agreeing that they will accept the result as adequate for the purpose of granting a degree. (Of course you will have to write the thesis in acceptable form, and you probably will discover things in the course of your research that were not anticipated but which should be addressed in your thesis, but the minimum core intellectual contribution of your thesis will be set by the proposal.) Both parties benefit from an agreed upon plan.

The objective in writing a proposal is to describe what you will do, why it should be done, how you will do it and what you expect will result. Being clear about these things from the beginning will help you complete your thesis in a timely fashion. A vague, weak or fuzzy proposal can lead to a long, painful, and often unsuccessful thesis writing exercise. A clean, well thought-out, proposal forms the backbone for the thesis itself. The structures are identical and through the miracle of word-processing, your proposal will probably become your thesis.

A good thesis proposal hinges on a good idea. Once you have a good idea, you can draft the proposal in an evening. Getting a good idea hinges on familiarity with the topic. This assumes a longer preparatory period of reading, observation, discussion, and incubation. Read everything that you can in your area of interest. Figure out what are the important and missing parts of our understanding. Figure out how to build/discover those pieces. Live and breathe the topic. Talk about it with anyone who is interested. Then just write the important parts as the proposal. Filling in the things that we do not know and that will help us know more: that is what research is all about.

Proposals help you estimate the size of a project. Don’t make the project too big. Our MA program statement used to say that a thesis is equivalent to a published paper in scope.

These days, sixty double spaced pages, with figures, tables and bibliography, would be a long paper. Your proposal will be shorter, perhaps five pages and certainly no more than fifteen pages. (For perspective, the NSF limits the length of proposal narratives to 15 pages, even when the request might be for multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars.) The merit of the proposal counts, not the weight. Shoot for five pithy pages that indicate to a relatively well-informed audience that you know the topic and how its logic hangs together, rather than fifteen or twenty pages that indicate that you have read a lot of things but not yet boiled it down to a set of prioritized linked questions.

This guide includes an outline that looks like a “fill-in the blanks model” and, while in the abstract all proposals are similar, each proposal will have its own particular variation on the basic theme. Each research project is different and each needs a specifically tailored proposal to bring it into focus. Different advisors, committees and agencies have different expectations and you should find out what these are as early as possible; ask your advisor for advice on this. Further, different types of thesis require slightly different proposals. What style of work is published in your sub-discipline?

Characterizing theses is difficult. Some theses are “straight science”. Some are essentially opinion pieces. Some are policy oriented. In the end, they may well all be interpretations of observations, and differentiated by the rules that constrain the interpretation. (Different advisors will have different preferences about the rules, the meta-discourse, in which we all work.)

In the abstract all proposals are very similar. They need to show a reasonably informed reader why a particular topic is important to address and how you will do it. To that end, a proposal needs to show how your work fits into what is already known about the topic and what new contribution your work will make. Specify the question that your research will answer, establish why it is a significant question, show how you are going to answer the question, and indicate what you expect we will learn. The proposal should situate the work in the literature, it should show why this is an (if not the most) important question to answer in the field, and convince your committee (the skeptical readers that they are) that your approach will in fact result in an answer to the question.

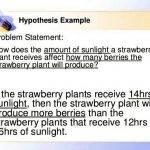

Theses which address research questions that can be answered by making plan-able observations (and applying hypothesis testing or model selection techniques) are preferred and perhaps the easiest to write. Because they address well-bounded topics, they can be very tight, but they do require more planning on the front end. Theses which are largely based on synthesis of observations, rumination, speculation, and opinion formation are harder to write, and usually not as convincing, often because they address questions which are not well-bounded and essentially unanswerable. (One ‘old saw’ about research in the social sciences is that the finding is always: “some do and some don’t”. Try to avoid such insight-less findings; finding “who do and who don’t” is better.) One problem with this type of project is that it is often impossible to tell when you are “done”. Another problem is that the nature of argument for a position rather than the reasoned rejection of alternatives to it encourages shepherding a favored notion rather than converging more directly toward a truth. (See Chamberlain’s and Platt’s articles). A good proposal helps one see and avoid these problems.

Literature review-based theses involve collection of information from the literature, distillation of it, and coming up with new insight on an issue. One problem with this type of research is that you might find the perfect succinct answer to your question on the night before (or after) you turn in the final draft — in someone else’s work. This certainly can knock the wind out of your sails. (But note that even a straight-ahead science thesis can have the problem of discovering, late in the game, that the work you have done or are doing has already been done; this is where familiarity with the relevant literature by both yourself and your committee members is important.)

Here is a model for a very brief (maybe five paragraph) proposal that you might use to interest faculty in sitting on your committee. People who are not yet hooked may especially appreciate its brevity.

In the first paragraph, the first sentence identifies the general topic area. The second sentence gives the research question, and the third sentence establishes its significance.

The next couple of paragraphs gives the larger historical perspective on the topic. Essentially list the major schools of thought on the topic and very briefly review the literature in the area with its major findings. Who has written on the topic and what have they found? Allocate about a sentence per important person or finding. Include any preliminary findings you have, and indicate what open questions are left. Restate your question in this context, showing how it fits into this larger picture.

The next paragraph describes your methodology. It tells how will you approach the question, what you will need to do it.

The final paragraph outlines your expected results, how you will interpret them, and how they will fit into the our larger understanding i.e. ‘the literature’.

The two outlines below are intended to show both what are the standard parts of a proposal and of a science paper. Notice that the only real difference is that you change “expected results” to “results” in the paper, and usually leave the budget out, of the paper.

Another outline (maybe from Gary Fuller?).

Each of these outlines is very similar. You probably see already that the proposal’s organization lends itself to word-processing right into the final thesis. It also makes it easy for readers to find relevant parts more easily. The section below goes into slightly more detail on what each of the points in the outline is and does.

A good title will clue the reader into the topic but it can not tell the whole story. Follow the title with a strong introduction. The introduction provides a brief overview that tells a fairly well informed (but perhaps non-specialist) reader what the proposal is about. It might be as short as a single page, but it should be very clearly written, and it should let one assess whether the research is relevant to their own. With luck it will hook the reader’s interest.

What is your proposal about? Setting the topical area is a start but you need more, and quickly. Get specific about what your research will address.

Once the topic is established, come right to the point. What are you doing? What specific issue or question will your work address? Very briefly (this is still the introduction) say how you will approach the work. What will we learn from your work?

Why is this work important? Show why this is it important to answer this question. What are the implications of doing it? How does it link to other knowledge? How does it stand to inform policy making? This should show how this project is significant to our body of knowledge. Why is it important to our understanding of the world? It should establish why I would want to read on. It should also tell me why I would want to support, or fund, the project.

State of our knowledge

The purpose of the literature review is to situate your research in the context of what is already known about a topic. It need not be exhaustive, it needs to show how your work will benefit the whole. It should provide the theoretical basis for your work, show what has been done in the area by others, and set the stage for your work.

In a literature review you should give the reader enough ties to the literature that they feel confident that you have found, read, and assimilated the literature in the field. It might do well to include a paragraph that summarizes each article’s contribution, and a bit of ‘mortar’ to hold the edifice together, perhaps these come from your notes while reading the material. The flow should probably move from the more general to the more focused studies, or perhaps use historical progression to develop the story. It need not be exhaustive; relevance is ‘key’.

This is where you present the holes in the knowledge that need to be plugged, and by doing so, situate your work. It is the place where you establish that your work will fit in and be significant to the discipline. This can be made easier if there is literature that comes out and says “Hey, this is a topic that needs to be treated! What is the answer to this question?” and you will sometimes see this type of piece in the literature. Perhaps there is a reason to read old AAG presidential addresses.

Your work to date

Tell what you have done so far. It might report preliminary studies that you have conducted to establish the feasibility of your research. It should give a sense that you are in a position to add to the body of knowledge.

Overview of approach

This section should make clear to the reader the way that you intend to approach the research question and the techniques and logic that you will use to address it.

This might include the field site description, a description of the instruments you will use, and particularly the data that you anticipate collecting. You may need to comment on site and resource accessibility in the time frame and budget that you have available, to demonstrate feasibility, but the emphasis in this section should be to fully describe specifically what data you will be using in your study. Part of the purpose of doing this is to detect flaws in the plan before they become problems in the research.

This should explain in some detail how you will manipulate the data that you assembled to get at the information that you will use to answer your question. It will include the statistical or other techniques and the tools that you will use in processing the data. It probably should also include an indication of the range of outcomes that you could reasonably expect from your observations.

In this section you should indicate how the anticipated outcomes will be interpreted to answer the research question. It is extremely beneficial to anticipate the range of outcomes from your analysis, and for each know what it will mean in terms of the answer to your question.

This section should give a good indication of what you expect to get out of the research. It should join the data analysis and possible outcomes to the theory and questions that you have raised. It will be a good place to summarize the significance of the work.

It is often useful from the very beginning of formulating your work to write one page for this section to focus your reasoning as you build the rest of the proposal.

This is the list of the relevant works. Some advisors like exhaustive lists. I think that the Graduate Division specifies that you call it “Bibliography”. Others like to see only the literature which you actually cite. Most fall in between: there is no reason to cite irrelevant literature but it may be useful to keep track of it even if only to say that it was examined and found to be irrelevant.

Use a standard format. Order the references alphabetically, and use “flag” paragraphs as per the University’s Guidelines.

Read. Read everything you can find in your area of interest. Read. Read. Read. Take notes, and talk to your advisor about the topic. If your advisor won’t talk to you, find another one or rely on ‘the net’ for intellectual interaction. Email has the advantage of forcing you to get your thoughts into written words that can be refined, edited and improved. It also gets time stamped records of when you submitted what to your advisor and how long it took to get a response.

Write about the topic a lot, and don’t be afraid to tear up (delete) passages that just don’t work. Often you can re-think and re-type faster than than you can edit your way out of a hopeless mess. The advantage is in the re-thinking.

Very early on, generate the research question, critical observation, interpretations of the possible outcomes, and the expected results. These are the core of the project and will help focus your reading and thinking. Modify them as needed as your understanding increases.

Use some systematic way of recording notes and bibliographic information from the very beginning. The classic approach is a deck of index cards. You can sort, regroup, layout spatial arrangements and work on the beach. Possibly a slight improvement is to use a word-processor file that contains bibliographic reference information and notes, quotes etc. that you take from the source. This can be sorted, searched, diced and sliced in your familiar word-processor. You may even print the index cards from the word-processor if you like the ability to physically re-arrange things.

Even better for some, is to use specialized bibliographic database software. Papyrus, EndNote, and other packages are available for PCs and MacIntoshs. The bib-refer and bibTex software on UNIX computers are also very handy and have the advantage of working with plain ASCII text files (no need to worry about getting at your information when the wordprocessor is several generations along). All of these tools link to various word-processors to make constructing and formating your final bibliography easier, but you won’t do that many times anyway. If they help you organize your notes and thinking, that is the benefit.

Another pointer is to keep in mind from the outset that this project is neither the last nor the greatest thing you will do in your life. It is just one step along the way. Get it done and get on with the next one. The length to shoot for is “equivalent to a published paper”, sixty pages of double spaced text, plus figures tables, table of contents, references, etc. is probably all you need. In practice, most theses try to do too much and become too long. Cover your topic, but don’t confuse it with too many loosely relevant side lines.

This is not complete and needs a little rearranging.

The balance between Introduction and Literature Review needs to be thought out. The reader will want to be able to figure out whether to read the proposal. The literature review should be sufficiently inclusive that the reader can tell where the bounds of knowledge lie. It should also show that the proposer knows what has been done in the field (and the methods used).

The balance may change between the proposal and the thesis. It is common, although not really desirable, for theses to make reference to every slightly related piece of work that can be found. This is not necessary. Refer to the work that actually is linked to your study, don’t go too far afield (unless your committee is adamant that you do ;-).

Krathwohl, David R. 1988. How to Prepare a Research Proposal: Guidelines for Funding and Dissertations in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Syracuse University Press.

Recent National Science Foundations Guidelines for Research Proposals can be found on the NSF website, nsf.gov.

Chamberlain, T.C. “The Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses”, reprinted in Science. Vol 148, pp754-759. 7 May 1965.

Platt, J. “Strong Inference” in Science. Number 3642, pp. 347-353, 16 October 1964.

Strunk and White The Elements of Style

Turabian, Kate. 1955 (or a more recent edition) A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations. University of Chicago Press.

Mortimer J. Adler and Charles Van Doren. 1940 (’67, ’72 etc). How to Read a Book. Simon and Schuster Publishers. New York City, NY.

Last edited: 16 December 2014

Writing a good thesis conclusion

Writing a good thesis conclusion Mini thesis title proposal on education

Mini thesis title proposal on education Writing rubric reflective essay thesis

Writing rubric reflective essay thesis If then because thesis proposal

If then because thesis proposal American dragon jake long professor rotwoods thesis writing

American dragon jake long professor rotwoods thesis writing