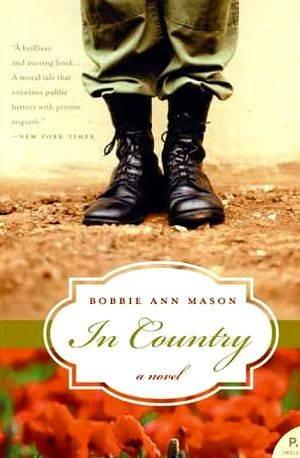

This detailed literature summary also contains Topics for Discussion on In Country by Bobbie Ann Mason.

In Country, by Bobbie Ann Mason, is a novel set in Hopewell, Kentucky in the summer of 1984. It is a coming-of-age story about a young girl, Sam Hughes, who has just finished high school and isn’t sure if she wants to stay in Hopewell.

Sam lives with her Uncle Emmett who struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder from his time fighting in the Vietnam War. Sam’s father was also in the war, but he died a month before Sam was born. Sam becomes increasingly interested in helping her uncle and learning about the war and her father.

Lonnie Malone, Sam’s boyfriend, goes away for his brother’s bachelor party and Sam goes to the Vietnam Veteran’s dance while he is away. Sam is constantly asking Emmett’s friends, who are also vets, what Vietnam was really like. She wants to know so that she can help Emmett solve his health issues—namely his adult acne which she fears is due to Agent Orange exposure as are the strange pains he gets in his head. As she gets to know more of the Vets, she develops a crush on Tom Hudson. While Lonnie is away, she goes to the vet’s dance and spends the night with Tom.

Sam learns Tom is impotent and is unsure if it is because of a physical injury from the war, but Tom tells her it is all in his mind. She worries Emmett might have a physical injury and that is why he is not married or not currently dating anyone.

Once Lonnie returns from his weekend away, Sam gives him back his ring and breaks up with him. She decides to visit her father’s parents to see if they have any pictures, letters or other mementos Sam can keep and help her make sense of who her dad was.

Her Mamaw gives her a diary that came home with her father’s body. Her grandparents said there is nothing in it, and the handwriting is too difficult to read.

Sam reads it anyway and finds her father’s journal entries about what happened while he was in Vietnam. She is disgusted by how her father sounded proud to kill the V.C. and how he talks about the Vietnamese in his writing. She thinks all vets are like this and decides she is going to spend a night in the local swamp to see what it feels like. Emmett comes looking for her. They talk about what it was like for Emmett, and finally, after 14 years of mourning, Emmett breaks down.

This section contains 436 words

(approx. 2 pages at 400 words per page)

Bobbie Ann Mason 1940-

American short story writer, novelist, and critic.

The following entry presents an overview of Mason’s career through 2001. For further information on her life and works, see CLC, Volumes 28, 43, and 82.

Considered a significant voice in southern literature, Mason has attracted a large degree of critical attention for her short stories and novels. Mason’s fiction, set primarily in rural western Kentucky, revolves around the central theme of social and cultural change in the region, and her characters typically find themselves in a continual state of upheaval caused by the change. Mason is known for her spare prose laced with numerous references to icons of popular culture, and she is recognized for her artfully crafted tales of self-realization set among blue-collar workers and country people.

Born in Mayfield, Kentucky, Mason has used her upbringing in the rural south as a backdrop for most of her fiction. Mason attended the University of Kentucky where she began to be exposed to a diverse range of authors including Thomas Wolfe, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and J. D. Salinger. She began her writing career as a journalist, working for the Mayfield Messenger during summers and the University of Kentucky student newspaper, the Kernel. After graduating, Mason moved to New York, where she worked for the Ideal Publishing Company, writing for magazines such as Movie Stars, Movie Life, and T.V. Star Parade. Although she enjoyed writing for publications covering aspects of popular culture, Mason chose to return to the academic world and earned a doctorate from the University of Connecticut in 1972. Her dissertation on Vladimir Nabokov’s novel Ada was published in 1974 as Nabokov’s Garden: A Guide to “Ada.” While at the University of Connecticut, Mason began writing short stories which she submitted to the New Yorker magazine. After twenty submissions, her first published story appeared in the magazine in 1980. That work, “Offerings,” was later reprinted in her collection Shiloh, and Other Stories (1982). Mason went on to write several novels, short story collections, and a memoir, establishing a promising literary career.

Mason’s first two collections of short fiction—Shiloh, and Other Stories and Love Life (1989)—employ present-tense narration to relate stories about characters torn between the world they have always known and their desire for change and independence. In these works and in longer pieces such as In Country (1985) and Spence + Lila (1988), Mason makes liberal use of references to popular culture icons, which she utilizes to illustrate her characters’ alienation from their heritage and family traditions. In the novel In Country, Mason’s heroine uses the music and lyrics of rock singer Bruce Springsteen to help define herself and come to grips with the legacy of the Vietnam War. In Spence + Lila, Mason focuses attention on the small, trivial aspects of life in a convincing portrayal of a long-married couple who battle through the wife’s ordeal with breast cancer. Spence and Lila have been married for over forty years and Lila’s upcoming surgery forces them to face the prospect of being separated for the first time since World War II. In the novel Feather Crowns (1993) Mason shifts her setting to the turn of the century. The work takes place in Kentucky in 1900 and follows a farm wife named Christianna Wheeler who gives birth to quintuplets. Overnight, the modest Wheeler tobacco farm becomes a haven for curious passers-by as people flock to see—and hold—the tiny babies. As events unfold, Christie and her husband find themselves drawn away from home as a carnival sideshow attraction. The book is a meditation upon fame, self-determination, and the conflict between superstition and science. Clear Springs (1999), Mason’s memoir, follows her adolescence in rural Kentucky and comments on the generation of Americans who were raised in the 1950s.

Critics have used terms such as “minimalism” and “dirty realism” to describe Mason’s writing style. Many reviewers have praised her use of simple prose peppered with Southern dialect and the trappings of contemporary life. Although Mason’s spare narrative style has been faulted by some reviewers, her skillful evocation of the details of everyday existence has been considered by most critics as her strongest asset. Other commentators have derided Mason’s writing for the authorial distance she maintains. These critics believe that her invisibility as an author causes difficulty in allowing readers to become involved in her stories. However, many reviewers have agreed that her characters’ moments of self-realization are executed with skill and grace, and that such moments override her tendency to distance herself from the works. Overall, critics have asserted that Mason’s stories are effective and entertaining.

Principal Works

SOURCE: Wilhelm, Albert E. “Private Rituals: Coping with Change in the Fiction of Bobbie Ann Mason.” Midwest Quarterly 28, no. 2 (winter 1987): 271–82.

[In the following essay, Wilhelm discusses the effects of social change on the lives of everyday people, a primary theme in Mason’s stories. ]

As her double given name might suggest, Bobbie Ann Mason was a Southern country girl who made her way to the sophisticated East. She grew up on a small dairy farm in Western Kentucky. Later she worked for a publishing company in New York City and earned graduate degrees from universities in New York and Connecticut. As a child she avidly read Nancy Drew and other girl-detective mysteries and as a young woman she published a critical study of Nabokov’s Ada. Her book of collected stories, Shiloh, and Other Stories (1982), won the Ernest Hemingway Award (for the year’s most distinguished first fiction) and was a finalist for the American Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. In the early 1970s Mason was a teacher at a small state college in Pennsylvania; now her own stories appear prominently in anthologies used in thousands of college classrooms. Mason’s critical reputation continues to grow, and her fictional world has been described by Maureen Ryan as “paradigmatic of the contemporary South” and much of modern America (294).

Such diverse biographical data may help one to appreciate a major theme in Mason’s fiction—the effects on ordinary people of rapid social change. Indeed most of her characters are residents of a typical “ruburb”—an area in Western Kentucky that is “no longer rural but not yet suburban” (Sheppard 88)—and they usually suffer the bewildering effects of future shock. A young woman in one story observes that one day she “was listening to Hank Williams and shelling corn for the chickens” while the next day she “was expected to know what wines went with what” (207). In another story a divorced mother laments the fact that families “shift memberships, like clubs” (167) and a stepfather is “like a substitute host on a talk show” (173). Almost all of Mason’s characters share, to some extent, the plight of the mentally retarded adults in “A New-Wave Format”; they “can’t keep up with today’s fast pace” and “need a world that is slowed down” (217).

Mason, of course, can document such problems because she too has experienced cultural dislocation. In an interview with Professor Yu Yuh-chao (Louisville, Kentucky, February 22, 1985), she contrasted her work with that of the writers of the Old South. “In the older generation,” she said, “there was a much stronger sense of the place of the South, sense of the family, and sense of the land. I guess the newer writers are writing about how that sense has been breaking down. … There is a difficulty retaining identity and integrity in the face of change.” Mason went on to compare her personal situation with that of Nabokov: “I was strongly influenced by his vision of things. … He was an exile and he carried around two cultures in his experience. I feel the same way about the South and the North and I feel like an exile.”

In describing her “ruburb,” then, Mason provides much more than sociological documentation. She is primarily interested in exploring the crises in individual lives that are provoked or intensified by radical changes in social relationships. To be sure, such crises are hardly new. Arnold van Gennep pointed out many years ago that “the life of any individual in any society is a series of passages … a succession of stages with similar ends and beginnings: birth, social puberty, marriage, fatherhood, advancement to a higher class, occupational specialization, and death” (2–3). In traditional societies, however, these transitions were usually marked by definite ceremonies which served to bridge the gap between old and new. Such rituals for “incorporating the individual into the group and returning him to the customary routines of life” helped to “cushion the disturbance” or buffer the shock which necessarily accompanied any transition (ix). In the society portrayed by Mason, though, one casualty of rapid change has been ritual itself. Painful transitions have become more frequent and more intense, but the adaptive and adjustive response previously offered by ritual is frequently lacking. In some of her stories Mason concentrates on certain universal and inevitable life crises like entering puberty and growing old—transitions for which specific rituals were once vital but are now largely abandoned. In other stories she deals with family crises like separation and divorce which have only recently become commonplace and for which most Western societies have never developed any adequate rituals. Thus, many of Mason’s characters suffer from what Orrin Klapp has termed “poverty of ritual” (126). In the absence of any clearly established common ceremonies, they must frequently improvise or develop impromptu ritual. Old rituals have become relics or “empty events”; any new rituals are often “despairingly privatized” (Klapp 137).

The story in Mason’s collection which is most explicitly concerned with a time of passage marked by specific rituals in traditional societies is “Detroit Skyline, 1949.” This story documents a rather confused and unceremonial passage from childhood to adolescence. In a pattern that is typical of many initiation stories, Peggy Jo leaves the protected environment of her farm home and journeys to the big city. For the innocent Peggy “everything about the North [is] confusing” (40). She is especially bewildered by Lunetta Jones whose elaborate clothes and thick lipstick (described as “man bait”) exude adult sexuality (40–41). To make matters worse, Peggy is alternately invited to grow up and exhorted to remain a child. When she watches Howdy Doody and Lucky Pup on television, her cousin says she is “too old for those baby shows” (41). When she expresses an interest in adult problems, she is told, “That don’t concern younguns” (43). In short, the initiate has no adequate guide to lead her through this uncertain urban landscape. In one key scene Peggy says that her mother “seemed as confused as I was” (49). Although Peggy experiences much that is new, her journey of self-discovery is surely incomplete. In fact, she never actually sees Detroit—only a fuzzy picture of its tall buildings on the TV screen. The climax of Peggy’s experiences is not her own rebirth but her mother’s miscarriage. Her mother loses the baby she didn’t know she had, and Peggy’s own search for a mature identity is abortive.

In “The Climber” Mason focuses on the problems of growing older and, specifically, on one individual’s frightening intimations of mortality. For Dolores that discovery of a lump in her breast portends a dramatic change, but, as her name suggests, she remains an isolated lady of sorrows who can share her fears with no one. The story begins with a comment about “walking with Jesus” (109), but TV evangelism has replaced any real community of believers. Instead of meaningful liturgy Dolores hears only a disco spiritual with no words other than the constantly repeated title. When Dolores needs supporting hands, the only ones she can visualize are those of Phil Donahue, and they are nothing more than dots of light on a video screen. The only ritual of reassurance in which Dolores can participate is her regular telephone conversation with her friend Dusty, but Dusty remains a disembodied voice who never actually appears in the story. In the absence of real ritual, Dolores tries to make her own. Like those who must deal with grief in Emily Dickinson’s poem “The Bustle in a House,” Dolores repeatedly performs the rituals of housecleaning. Later, after her doctor assures her that she has fibrocystic disease rather than cancer, she is happy that he prescribes a strict diet. In her formless world this diet will provide a “welcome guide for living, something certain” (119). At the same time, however, she feels slightly cheated. Her brush with death has not really been a significant existential crisis since the threat has not been strong enough to provoke a real.

(The entire section is 3403 words.)

Get Free Access

Start your free trial with eNotes for complete access to this resource and thousands more.

University of the philippines list of thesis and dissertations

University of the philippines list of thesis and dissertations Heaven and earth in jest thesis proposal

Heaven and earth in jest thesis proposal Font type phd thesis writing

Font type phd thesis writing The glass menagerie essay thesis writing

The glass menagerie essay thesis writing Thesis writing services philippines news

Thesis writing services philippines news