24. Introduction and Conclusion.

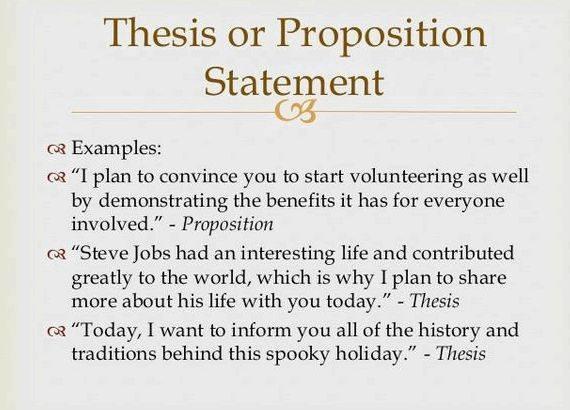

These represent the most serious omission students regularly make. Every essay or paper designed to be persuasive needs a paragraph at the very outset introducing both the subject at hand and the thesis which is being advanced. It also needs a final paragraph summarizing what’s been said and driving the author’s argument home.

These are not arbitrary requirements. Introductions and conclusions are crucial in persuasive writing. They put the facts to be cited into a coherent structure and give them meaning. Even more important, they make the argument readily accessible to readers and remind them of that purpose from start to end.

Think of it this way. As the writer of an essay, you’re essentially a lawyer arguing in behalf of a client (your thesis) before a judge (the reader) who will decide the case (agree or disagree with you). So, begin as a lawyer would, by laying out the facts to the judge in the way you think it will help your client best. Like lawyers in court, you should make an opening statement, in this case, an introduction. Then review the facts of the case in detail just as lawyers question witnesses and submit evidence during a trial. This process of presentation and cross-examination is equivalent to the body of your essay. Finally, end with a closing statement&-that is, the conclusion of your essay&-arguing as strongly as possible in favor of your client’s case, namely, your theme.

Likewise, there are several things your paper is not. It’s not a murder mystery, for instance, full of surprising plot twists or unexpected revelations. Those really don’t go over well in this arena. Instead, lay everything out ahead of time so the reader can follow your argument easily.

Nor is a history paper an action movie with exciting chases down dark corridors where the reader has no idea how things are going to end. In academic writing it’s best to tell the reader from the outset what your conclusion will be. This, too, makes your argument easier to follow. Finally, it’s not a love letter. Lush sentiment and starry-eyed praise don’t work well here. They make it look like your emotions are in control, not your intellect, and that will do you little good in this enterprise where facts, not dreams, rule.

All in all, persuasive writing grips the reader though its clarity and the force with which the data bring home the thesis. The point is to give your readers no choice but to adopt your way of seeing things, to lay out your theme so strongly they have to agree with you. That means you must be clear, forthright and logical. That’s the way good lawyers win their cases.

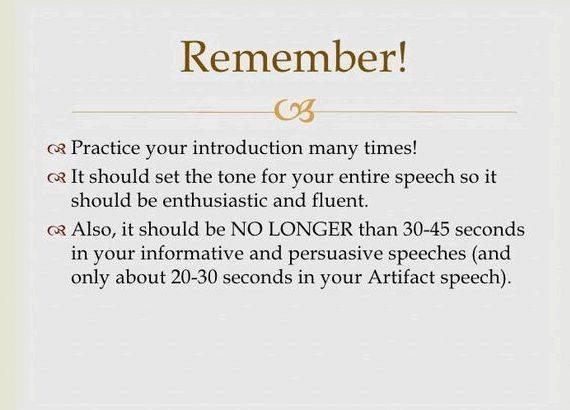

A. How to Write an Introduction. The introduction of a persuasive essay or paper must be substantial. Having finished it, the reader ought to have a very clear idea of the author’s purpose in writing. To wit, after reading the introduction, I tend to stop and ask myself where I think the rest of the paper is headed, what the individual paragraphs in its body will address and what the general nature of the conclusion will be. If I’m right, it’s because the introduction has laid out in clear and detailed fashion the theme and the general facts which the author will use to support it.

Let me give you an example of what I mean. The following is an introduction of what turned out to be a well-written paper, but the introduction was severely lacking:

The role of women has changed over the centuries, and it has also differed from civilization to civilization. Some societies have treated women much like property, while others have allowed women to have great influence and power.

Not a bad introduction really, but rather scant. I have no idea, for instance, which societies will be discussed or what the theme of the paper will be. That is, while I can see what the general topic is, I still don’t know the way the writer will draw the facts together, or even really what the paper is arguing in favor of.

As it turned out, the author of this paper discussed women in ancient Egypt, classical Greece, medieval France and early Islamic civilization and stressed their variable treatment in these societies. This writer also focused on the political, social and economic roles women have played in Western cultures and the various ways they have found to assert themselves and circumvent opposition based on gender.

Given that, I would rewrite the introduction this way:

The role of women in Western society has changed dramatically over the centuries, from the repression of ancient Greece to the relative freedom of women living in Medieval France. The treatment of women has also differed from civilization to civilization even at the same period in history . Some societies such as Islamic ones have treated women much like property, while others like ancient Egypt have allowed women to have great influence and power. This paper will trace the development of women’s rights and powers from ancient Egypt to late medieval France and explore their changing political, social and economic situation through time. All the various means women have used to assert themselves show the different ways they have fought against repression and established themselves in authority.

Now it is clear which societies will be discussed (Egypt, Greece, France, Islam) and what the general theme of the paper will be (the variable paths to empowerment women have found over time). Now I know where this paper is going and what it’s really about.

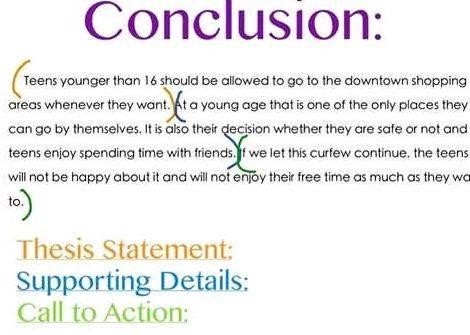

B. How to Write a Conclusion. In much the same way that the introduction lays out the thesis for the reader, the conclusion of the paper should reiterate the main points&-it should never introduce new ideas or things not discussed in the body of the paper!&-and bring the argument home. The force with which you express the theme here is especially important, because if you’re ever going to convince the reader that your thesis has merit, it will be in the conclusion. In other words, just as lawyers win their cases in the closing argument, this is the point where you’ll persuade others to adopt your thesis.

If the theme is clear and makes sense, the conclusion ought to be very easy to write. Simply begin by restating the theme, then review the facts you cited in the body of the paper in support of your ideas&-and it’s advisable to rehearse them in some detail&-and end with a final reiteration of the theme. Try, however, not to repeat the exact language you used elsewhere in the paper, especially the introduction, or it will look like you haven’t explored all aspects of the situation (see above, #7 ).

All in all, remember these are the last words your reader will hear from you before passing judgment on your argument. Make them as focused and forceful as possible.

Though expectations vary from one discipline to the next, the conclusion of your paper is generally a place to explore the implications of your topic or argument. In other words, the end of your paper is a place to look outward or ahead in order to explain why you made the points you did.

Writing the Conclusion

In the past, you may have been told that your conclusion should summarize what you have already said by restating your thesis and main points. It is often helpful to restate your argument in the conclusion, particularly in a longer paper, but most professors and instructors want students to go beyond simply repeating what they have already said. Restating your thesis is just a short first part of your conclusion. Make sure that you are not simply repeating yourself; your restated thesis should use new and interesting language.

After you have restated your thesis, you should not just summarize the key points of your argument. Your conclusion should offer the reader something new to think about–or, at the very least, it should offer the reader a new way of thinking about what you have said in your paper.

You can employ one of several strategies for taking your conclusion that important step further:

- Answer the question, “So what?”

- Connect to a larger theme from the course

- Complicate your claim with an outside source

- Pose a new research question as a result of your paper’s findings

- Address the limitations of your argument

The strategy you employ in writing a conclusion for your paper may depend upon a number of factors:

- The conventions of the discipline in which you are writing

- The tone of your paper (whether your paper is analytical, argumentative, explanatory, etc.)

- Whether your paper is meant to be formal or informal

Choose a strategy that best maintains the flow and tone of your paper while allowing you to adequately tie together all aspects of your paper.

The Final “So what?” Strategy

Part of generating a thesis statement sometimes requires answering the “so what?” question–that is, explaining the significance of your basic assertion. When you use the “so what?” strategy to write your conclusion, you are considering what some of the implications of your argument might be beyond the points already made in your paper. This strategy allows you to leave readers with an understanding of why your argument is important in a broader context or how it can apply to a larger concept.

For example, consider a paper about alcohol abuse in universities. If the paper argues that alcohol abuse among students depends more on psychological factors than simply the availability of alcohol on campus, a “so what?” conclusion might tie together threads from the body of the paper to suggest that universities are not approaching alcohol education from the most effective perspective when they focus exclusively on limiting students’ access to alcohol.

To use this strategy, ask yourself, “How does my argument affect how I approach the text or issue?”

The “Connecting to a Course Theme” Strategy

When you use the “connecting to a course theme” strategy to write your conclusion, you are establishing a connection between your paper’s thesis and a larger theme or idea from the course for which you are writing your paper.

For example, consider a paper about mothers and daughters in Eudora Welty’s Delta Wedding for a class called “The Inescapable South.” This paper argues that a strong dependence on the mother is analogous to a strong dependence on the South. A “connecting to a course theme” conclusion for this paper might propose that Welty’s daughter characters demonstrate what type of people can and cannot escape the South.

To use this strategy, ask yourself, “What is an overall theme of this course? How does my paper’s thesis connect?”

The “Complicating Your Claim” Strategy

When you use the “complicating your claim” strategy to write your conclusion, you are using one or more additional resources to develop a more nuanced final thesis. Such additional resources could include a new outside source or textual evidence that seemingly contradicts your argument.

For example, consider a paper about Ireland’s neutrality during World War II. This paper argues that Ireland refused to enter the war because it wanted to assert its sovereignty, not because it had no opinion about the conflict. A “complicating your claim” conclusion for this paper might provide historical evidence that Ireland did aid the Allies, suggesting that the Irish were more influenced by international diplomacy than their formal neutrality might suggest.

To use this strategy, ask yourself, “Is there any evidence against my thesis?” or “What does an outside source have to say about my thesis?”

The “Posing a New Question” Strategy

When you use the “posing a new question” strategy to write your conclusion, you are inviting the reader to consider a new idea or question that has appeared as a result of your argument.

For example, consider a paper about three versions of the folktale “Rapunzel.” This paper argues that German, Italian, and Filipino versions of “Rapunzel” all vary in terms of characterization, plot development, and moral, and as a result have different themes. A “posing a new question” conclusion for this paper might ask the historical and cultural reasons for how three separate cultures developed such similar stories with such different themes.

To use this strategy, ask yourself, “What new question has developed out of my argument?”

The “Addressing Limitations” Strategy

When you use the “addressing limitations” strategy to write your conclusion, you are discussing the possible weaknesses of your argument and, thus, the fallibility of your overall conclusion. This strategy is often useful in concluding papers on scientific studies and experiments.

For example, consider a paper about an apparent correlation between religious belief and support for terrorism. An “addressing limitations” conclusion for this paper might suggest that the apparent correlation relies on the paper’s definition of “terrorism” and, since the definition is not objective, the apparent correlation might have been wrongly identified.

To use this strategy, ask yourself, “In what aspects is my argument lacking? Are there circumstances in which my conclusions might be wrong?”

Polishing Your Conclusion–and Your Paper

After you’ve completed your conclusion, look over what you have written and consider making some small changes to promote clarity and originality:

- Unless your discipline requires them, remove obvious transitions like “in conclusion,” “in summary,” and “in result” from your conclusion; they get in the way of the actual substance of your conclusion.

- Consider taking a strong phrase from your conclusion and using it as the title or subtitle of your paper.

Also, be sure to proofread your conclusion carefully for errors and typos. You should double-check your entire paper for accuracy and correct spelling as well.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

wts/shtml_navs/iub.jpg” />

Writing Tutorial Services

Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning

Wells Library Learning Commons, 1320 E. Tenth St. Bloomington, IN 47405

Phone: (812) 855-6738

Comments

Writing a phd thesis in word

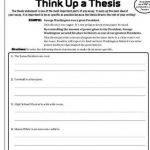

Writing a phd thesis in word Thesis writing practice for middle school

Thesis writing practice for middle school Photonic crystal biosensor thesis writing

Photonic crystal biosensor thesis writing Progress alan lightman thesis proposal

Progress alan lightman thesis proposal American insurgents american patriots thesis writing

American insurgents american patriots thesis writing