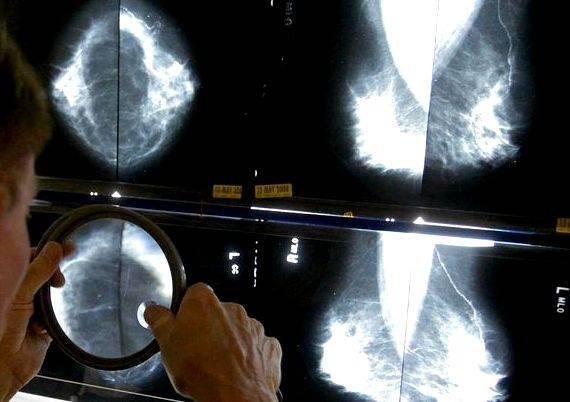

The controversy over when a woman should get mammograms is about to heat up again.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel of experts whose members are appointed by the federal government, issued a final set of recommendations late Monday saying that women between the ages of 50 and 74 should get routine screening once every two years. The task force’s guidelines are important because insurers and government programs often follow the panel’s recommendations in deciding whether to cover certain preventive services.

The task force’s final recommendation is likely to be controversial because some other groups say the screening should start earlier. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, for example, recommends that regular screenings begin at age 40, while the American Cancer Society calls for women to start yearly screening at age 45 and then move to screening every two years starting at age 55.

Congress has sided with proponents of earlier screening. Last month, in anticipation of Monday’s release of the task force’s final recommendation, lawmakers took preemptive action: It directed insurers to ignore the task force’s latest guidelines and, instead, to rely on its 2002 recommendation. That called for annual mammograms to begin at 40. As a result of the congressional action, women in their 40s will continue to be able to get annual mammograms at no cost.

The differences over when to start regular screening reflect the growing concern that the benefits of mammograms may have been oversold, and that they don’t outweigh the anxiety and potential harm caused by over-diagnosis and false positives from the tests.

The debate over when to start regular screening involves only women of “average risk” who don’t have specific risk factors for breast cancer such as the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations or a family history of the disease. They’re also not aimed at diagnostic mammography, which takes place once a woman has a symptom such as a lump. The screening recommendations are not binding on doctors, hospitals or insurers.

In releasing its final recommendations, the task force confirmed an earlier guidance it issued that said screening mammography had the greatest benefit for women ages 50 to 74. For women in their 40s, the likelihood of benefit is less and the potential harms are proportionally greater, it said. The most serious potential harm is unneeded treatment for a type of cancer that would not have become a threat to a woman’s health during her lifetime.

The congressional action, which was included in the recently enacted spending law, has drawn criticism from some experts.

“The U.S. Congress thinks it’s perfectly acceptable, even preferred, for a scientific document from 14 years ago to guide coverage policy on screening for breast cancer in women,” says Kenneth Lin, a Georgetown University family medicine doctor who teaches preventive and evidence-based medicine.

Part of the problem is the common perception that women deserve free mammogram coverage and that the scientific community is basing its decision on cost or rationing, said Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University law professor and expert on public health.

Fran Visco, president of the National Breast Cancer Coalition, said the task force’s guidelines for women in their 40s — that they should discuss whether to get mammograms with their doctors and make individual decisions — come closest to following the evidence accumulated over the past three decades. Women should trust that process, she said.

Despite the decades of marketing of mammography to women, “women are capable of understanding the complexities of the issue, evaluating the evidence and making their own health decisions,” she said in a statement.

“At some point we will have to decide that we are not going to pay for interventions that lack a high level of medical evidence,” she said. “At this time, what does concern us very much are attempts by Congress to interfere with the makeup and process of the US Preventive Services Task Force.”

The task force first suggested in 2009 that breast cancer screening begin at 50 instead of 40, touching off enormous criticism. In 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, which required that certain preventive services be provided for free — if those services got a strong recommendation from the task force. But it included an amendment that effectively directed insurers to use the 2002 recommendations for mammograms. That meant that women who were 40 and older could get mammograms at no cost.

In April 2015, the task force came out with its latest draft guidance, basically reaffirming its 2009 recommendations that the greatest benefit of mammography screening is for women between 50 and 74.

Worried that millions of women under 50 could lose their free annual mammogram coverage if the guidelines became final, several health-care groups, including ACOG, the American College of Radiology and the Susan G. Komen Foundation, lobbied Congress to block that from happening.

Language was included in the spending bill that says any recommendations of the task force related to breast cancer screening, mammography and prevention refers to those “issued before 2009.”

Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) was among the lawmakers who pushed for the language to be included. In a statement, she said her number one priority was to ensure that women can get mammograms if they and their doctors decide it’s the right thing to do. “This means making sure that cost is not a deterrent to care,” she said.

Several groups that lobbied for congressional action said in a statement last month that the task force recommendations conflict with those of other organizations. This results in confusion and puts more than 22 million women at risk of losing of losing insurance coverage for mammograms.

This post has been updated.

Writing a newspaper article year 6000

Writing a newspaper article year 6000 Article writing on grow more trees

Article writing on grow more trees Articles on writing a systematic review

Articles on writing a systematic review Article writing bangla tutorial excel

Article writing bangla tutorial excel Writing article titles in apa

Writing article titles in apa