To use the sharing features on this page, please enable JavaScript.

Medical concepts and language can be complex. People need easily understandable health information regardless of age, background or reading level. MedlinePlus offers guidelines and resources to help you create easy-to-read health materials.

What are easy-to-read (ETR) materials?

ETR materials are written for audiences who have difficulty reading or understanding information. These materials can also benefit people who prefer reading easy-to-read information.

How do you create easy-to-read materials?

Writing ETR materials involves several important steps:

Step 1: Plan and Research

Know your target audience. Consider reading level, cultural background, age group and English Language Proficiency (ELP).

- Determine the target audience. Who do you expect to read your health materials?

- Research your target audience. Use tools such as databases, demographic information, surveys and interviews to learn about the needs of the target group. If extensive research is not possible due to time or budget constraints, try contacting other organizations that have similar target audiences.

- Include your target audience. Bring members of your audience into early planning stages. Users can provide valuable feedback.

- Determine objectives and outcomes. What do you want your target audience to do as a result of reading your materials? For example, if your objective is to show the proper use of asthma inhalers, emphasize the outcome of their proper use. A sample sentence might be: Following the directions for your asthma inhaler may help you to breathe easier.

- Learn about users with limited literacy skills. To write easy-to-read health materials, it’s important to learn about cognitive and reading challenges that some users may have. See What We Know About Users with Limited Literacy Skills in the Office on Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Health Literacy Online publication.

Step 2: Organize and Write

- Now that you have learned about your audience, consider them carefully when writing. Cultural, age, and gender differences may have an impact on your content. For example, the writing style and graphics may be different for an HIV/AIDS brochure for teens than for adults over age 50.

- Keep within a range of about a 7th or 8th grade reading level.

- Grab your readers’ attention from the very beginning. Make the first few sentences stand out by using compelling, clear language.

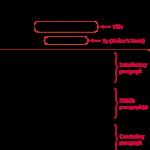

- Structure the material logically. Start by stating the topic. Include the most important points about what you want people to learn. Then write the body of the material. Finish with a summary of the material and restate the key concepts.

- Include specific actions users can take. Emphasize the benefits of taking action. For example, “Proper use of asthma inhalers helps you breathe better.”

- Examples and stories help engage readers.

- Avoid making assumptions about people who read at a limited level. Don’t talk down to the reader. Maintain an adult perspective while using easy-to-read language.

- Write your draft, then review and edit several times. Remove words, sentences or paragraphs that do not help the reader understand the concepts. Materials that are too wordy will make them more difficult to understand.

- Consider incorporating Web accessibility best practices. An accessible Web site helps people with reading and learning disabilities. For more information on Web accessibility, see the WebAIM (Web Accessibility in Mind) site from the Center for Persons with Disabilities at Utah State University.

Language and writing style

- Find alternatives for complex words, medical jargon, abbreviations, and acronyms. At times there may not be an alternative or you may want to teach patients the terms because their healthcare providers will be using them. In those cases, teach the terms by explaining the concept first in plain language. Then introduce the new word(s). It is also helpful to provide a simple pronunciation guide. For example, A normal heart beat starts in the upper right chamber of the heart, or atrium (ay -tree-yim).

- Avoid abstract language in giving instructions for actions. For example, instead of “Don’t lift anything heavy,” use “Don’t lift anything heavier than a gallon of milk (about 10 pounds).”

- Use varied sentence length to make the material interesting, but keep sentences simple. A general guideline is to limit most sentences to 10-15 words.

- Use words like “you” instead of “the patient”. A personal voice can help engage readers.

- Where appropriate, use bulleted lists instead of blocks of text to make information more readable. Dense blocks of text can be difficult to read.

- Use the active voice. Direct language helps people associate concepts with actions. Example:

Active: Amanda used her inhaler today.

Passive: The inhaler was used by Amanda today. - Be consistent with terms. For example, using “drugs” and “medications” interchangeably in the same document can cause confusion.

- When possible, say things in a positive way. For example, use “Eat less red meat” instead of “Don’t eat lots of red meat.”

Visual Presentation and Representation

- Use colors that are appealing to your target audience. Be aware, however, that some people may have vision disabilities. For example, some people with color blindness cannot distinguish red from green.

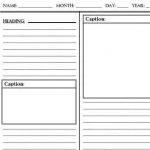

- Use illustrations and photos with concise captions. Keep captions close to images.

- Avoid graphs and charts unless they are essential to convey the concepts. If you do use them, make sure they are simple and clear.

- Balance the use of text, graphics, and clear or “white space”. Try for about 40-50% white space.

- Avoid italics of more than a few words at a time.

- Use sans serif fonts such as Arial, Verdana, Frutiger, Tahoma, or Helvetica. San serif fonts are considered easy to read even at smaller sizes. Also see the font accessibility page from WebAIM.

- Use bolded headings and subheadings to separate and highlight document sections.

- Justify the left margin only. This means the left margin should be straight and the right margin should be “ragged.”

- Use column widths of about 30-50 characters long (including spaces).

- Text on top of shaded backgrounds, photos, or patterns can be difficult to read and may also be inaccessible to many users with disabilities.

Step 3: Evaluate and Improve

Test your materials on a few individuals or a sample group from your target audience. Testing during the writing process can help ensure your audience understands your materials. Evaluate the feedback and revise your materials if necessary. For more information, see the Pretest and Revise Draft Materials section from the National Institute of Health’s “Clear and Simple” publication or go Part 6 of the Toolkit for Making Written Material Clear and Effective from the Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services.

Also test your materials with readability assessment testing tools to determine reading level. These are some examples:

- Readability-Score.com – An online tool from the open source Text Statistics project. Tests for 5 different reading assessment formulas.

- New Dale-Chall Readability formula – Designed for evaluating health education materials. Dale-Chall evaluates readability by assessing sentence structure and vocabulary.

- Fry Readability Graph – A commonly used readability assessment tool. See the Iowa Department of Public Health’s Fry Readability Graph page (PDF).

- SMOG – Less frequently used than the Fry Graph, but still widely used. An online testing tool is available at the Readability-Score.com site.

- Gunning FOG – One of the first readability tools. It is widely used. See the Iowa Department of Public Health’s Gunning-FOG Readability page (PDF). An online testing tool is available at the Readability-Score.com site.

- Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level – Used in the Microsoft Word grammar checker. An online testing tool is available at the Readability-Score.com site.

Readability software programs

Below are examples of software programs. Readability software may not be suitable for every ETR project but can be helpful for some.

- Health Literacy Advisor by Health Literacy Innovations (Add-on to Microsoft Word)

- TextQuest by Social Science Consulting (Windows and Mac)

- Readability Studio by Oleander Software (Windows and OSX)

- Stylewriter by Editor Software (Windows)

- UNIX commands to help identify readability and style issues

If you use a website or software program to test readability, you’ll need to prepare your text. You may have problems with reliability and accuracy if you don’t clean up your text first.

Be sure to go through the document and remove:

- headings

- sentence fragments

- lists with bullets (if bullets are complete sentences, you can use them in your sample)

- periods that don’t mark the end of a sentence, such as numerals in a numbered list (1. or 2.); abbreviations (Jill M. Sanchez, M..D. or Q. A.); periods in e.g. or i.e.; decimals (98.6 degrees or 12.9%); or periods in times (9 a.m.)

If you don’t remove extra periods, the testing tool or software may see many more sentences than are really there. This will artificially lower the readability score.

Step 4: Inform Us and Stay Informed

After you create ETR materials, we suggest you label them easy-to-read. MedlinePlus does not evaluate materials for reading level and will only display materials as easy-to-read only if the sponsoring organization labels them as such.

Other Resources

Sites with easy-to-read health materials

- National Institute of Diabetes Digestive Kidney Diseases has many easy-to-read resources in English and Spanish.

- National Institute of Mental Health has an easy-to-read publications page .

Guides, tools, articles and bibliographies for developing easy-to-read materials

- National Institutes of Health: Plain Language at NIH – Information and listings of training materials and other resources

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion – Health Literacy Online: A Guide to Writing and Designing Easy-to-Use Health Web Sites. Guide on creating easy-to use, user-centered Web sites and information on creating actionable health materials

- National Library of Medicine: MEDLINE/PubMed Search and Health Literacy Information Resources – Includes PubMED search strategy to find health literacy journal articles and health literacy information resources

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP): Health Literacy Online: A Guide for Simplifying the User Experience – Guide to creating limited-literacy health Web sites and Web content

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health Literacy – Collection of information and tools to improve health literacy

- Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services: Toolkit for Making Written Material Clear and Effective – 11-part downloadable toolkit has a comprehensive set of readability tools

- Clear Simple: Developing Effective Print Materials for Low-Literate Readers – Information on how to develop limited-literacy materials

- Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN): Plainlanguage.gov – Tips and tools, samples of writing, guidelines, and training. Includes online training course Plain Language: Getting Started or Brushing Up

- Group Health Research Institute: Program for Readability in Science Medicine (PRISM) – Two resources: PRISM Readability Toolkit (PDF) and PRISM Online Training (online training module requires registration)

- University of New Mexico Hospitals: Health Literacy – A number of resources, tools, and information on health literacy

- Sameer Badarudeen, MD and Sanjeev Sabharwal: Readability of Patient Education Materials: Current Role in Orthopaedics – Article is aimed at orthopaedics literature but general enough to apply to readability of other health or medical materials

- WebAIM: Writing Clearly and Simply – Guide on accessibility and readability of Web content

Thesauri and Dictionaries for Easier to Understand Health and Medical Words/Phrases

Note: NLM makes no endorsements or guarantees by displaying examples of software, online tools, or other resources.

Creative writing articles pdf file

Creative writing articles pdf file Feature writing tagalog articles philippines

Feature writing tagalog articles philippines Investing advice articles on writing

Investing advice articles on writing Article writing samples cbse results

Article writing samples cbse results Writing a news article esl worksheet

Writing a news article esl worksheet