By Rob Flumignan

Probably the toughest part about writing a mystery comes when you�ve got three hundred or so pages stacked up and it�s time to tie all the ends together and reveal whodunit. Though there really isn�t any easy way to tackle the unique and complex mystery form, there is a way to make the process slightly less like performing brain surgery with a pair of crochet needles.

Rather than dash willy-nilly through a first draft, praying to Edgar Allen Poe that your sleuth can piece together some clues and convincingly prove the butler did it, I suggest making sure you have the right clues to begin with. Like sign posts, clues can guide you through the complex journey of your mystery novel and make sure you reach the end without getting lost.

Yet traveling from sign to sign is not enough. You must make sure the signs you read (or plot) lead to your destination. In other words, before you figure out your sign posts (clues) you should decide where you’re going first.

My advice is to.

Start By Killing Someone

If you are writing a murder mystery, the killer and victim are probably the two most important characters in the novel. Some believe the sleuth is number one, but a sleuth without a murder is like a Happy Meal without a toy.

You can start with either victim or killer. Just make sure you create real and vivid people. Many a mystery is ruined by paper-thin villains and transparent victims.

I won’t go into detail on creating victim and killer since that would end up a whole article in itself. For now, realize that these characters are the fuel for our journey; they’re what keeps the mystery story humming.

They also determine your beginning and end. A mystery starts with a murder and ends when the killer is revealed.

Ask questions, fleshing out your killer and victim. Who, what, where, when, and (all important in the mystery) why? Don’t forget how, either. Pay particular attention to the relationship between these characters. Mysteries are often about revealing hidden connections between characters.

Selecting A Sleuth

If killer and victim make up the fuel for your murder mystery, the sleuth is your engine. He or she is what drives the story forward, carrying the reader along to the climax and revelation of the killer. Our destination.

You might already have an idea of the character you want to use as a sleuth, perhaps with plans of making a series for him or her. If you don’t, that’s okay. What’s good about the mystery’s holy trinity (Sleuth, Killer, Victim) is that developing one often leads to ideas for the others. Remember how I suggested looking for connections between killer and victim? Now it’s time to create connections between the sleuth and the killer or victim (or both).

You can�t just have your character watching TV, see a murder case covered on the news and decide, oh, I think I�ll go and investigate. No one�s going to buy that. And it won�t make for a dramatic story. If you�re doing the series detective, this connection-making will be a bit harder, but it�s twice as important in order to keep things believable.

The connection between your victim and sleuth might, however, be more personal than professional.

In Harlan Coben’s fantastic thriller, Tell No One ( Dell Pub Co; ISBN: 0440236703) the victim is his beloved wife. In my last novel, Crystal Past. the victim is the main character’s estranged ex-girlfriend as well as the one who helped him kick his drug habit. She’s a symbol of innocence to him and when he finds out she’s been killed while apparently turning tricks in downtown Detroit, he can’t help but seek the truth behind her murder.

Keep in mind when I say connection I�m not talking only about blood relationships or even casual acquaintance. There just has to be something that pulls killer, victim, and sleuth together. With the sleuth, it can be a client if he or she is a pro detective. But then you must think of ways to motivate your detective to take that particular case. This is part of creating a moving and original mystery. Finding clever ways to connect the power-players of your story will lead you to creative ideas and tight drama. Then, once you�ve made these connections, you�re ready to start laying out some clues.

Before going into how to use clues to plot your mystery, I’d like to take a moment to discuss the different kinds of clues you may use. I’ve tried to split them into three categories, though in many cases they overlap.

These are the other main characters in your story. In the mystery, everyone is a suspect to the reader, even if you don�t mean them to be. Often times your sleuth�s best friend will be the reader’s first suspect. Unless yours is another installment in an established series, the mystery reader won�t trust anyone in your cast. This is a good thing if you use it to your advantage, leading to some sneaky red herrings (discussed later).

Suspects are going to give you the most meat for your story in terms of plot. A lot of a mystery is the sleuth�s meeting with suspects and trying to weasel information out of them. Give every suspect a secret to hide and you�re in for some good conflict and plenty of plot.

Come up with a cast-list of suspects. Work out your connections with this list. Who hated the victim? Who loved the victim? Whom did the victim love and hate? Try to link everyone in some way, and give most everyone a reason to kill the victim.

Use your killer as a guide in creating your suspects. Find places where the killer might look innocent, then make a suspect look guilty in that way. For example, if your killer stands to gain nothing monetarily from the victim’s death, make a suspect the primary beneficiary of the victim’s $100,000 life insurance policy.

Once you�ve got a suspect line-up you can start thinking about scenes to introduce them and have them meet with your sleuth. Concentrate on how those encounters establish connections or reveal crucial information. Forget about sub-plot material for now.

While a great number of your clues will present themselves as such when your sleuth (and reader) finds them, there are other kinds of clues that appear quite useless when first encountered. I call these subliminal plants. The writer knows their clues, but the sleuth and reader do not. Not yet, at least.

These are very important when it comes to keeping the mystery unsolved until the end, yet still providing a believable climax when it comes. This is the innocuous detail you stick in with a number of other things so the reader reads right past without suspecting the item’s importance. The butcher block with the missing blade. Or the dog that didn’t bark. Sprinkle these throughout and then use a reversal where the sleuth remembers all these plants and puts the puzzle together.

The trick with subliminal plants is that many of them get mixed up with red herrings. Your reader will have to pay very close attention to every little item or bit of dialogue you drop into your story. Many of these clues will lead to the killer, but many more will lead both sleuth and reader astray.

A staple of every mystery novel is the red herring. The only difference between a red herring and a regular clue is the red herring points away from the killer, not toward him or her. Red herrings are important in that they keep the murder from being solved too easily, creating a great amount of plot when your sleuth wanders into blind allies.

However, if you’re plotting your mystery with clues, it’s important to get your real clues down first. Chart a clue path straight from murder to revelation. Then, after that’s done, and you’re certain your crime actually can be solved, start twisting the plot with red herrings. Use your real clues as guides. If you know that Colonel Mustard did it with the lead pipe in the library, make sure Professor Plumb was seen with the lead pipe in the ballroom.

Mapping The Journey

We’ve got our fuel (killer + victim) and our engine (the sleuth). We also formed an idea about our destination when we developed our killer. Now, with an idea of the kinds of clues available, it’s time to chart the journey. Remember, the clues are the signposts along the road. They will guide us from the beginning, where the murder is committed, to the end, where the killer is revealed.

First, think of your destination. Imagine your sleuth revealing the killer, the climax where it all goes down and justice is done. Our goal is to trace back from the end what elements need to be present in order for your sleuth to make that revelation. How does the sleuth realize the truth? Work backward. What is the last thing the sleuth discovers that changes his or her mind about everything he believed before?

Take another step back from there. What led the sleuth to go to that last piece of evidence? Something someone said? An object found? Keep working backward until you get stuck.

Now skip around. Brainstorm by clustering or jotting quick lists off the top of your head, just trying to come up with clues that will lead the sleuth to the truth.

Try looking at the beginning, the crime scene. Will your sleuth have access to the crime scene? What bits of evidence can you plant around the body that can come into play later?

Another tool you might want to consider are reversals. Big ones. Say your sleuth starts the story believing one theory and traces clues along those lines until, bam. she discovers something that wipes out everything she believed to be true up until then. Now she follows a different direction, until something else spins her around and she again must reevaluate what she thinks she knows about the murder.

You can use these reversals to anchor the main story line, splitting your story into manageable sections. Use these sections to group smaller clues in between, each clue leading to the next reversal. Work from large to small. Macro to micro.

I suggested clustering. You might also want to try using index cards with a clue per card, and perhaps a different color card for red herrings and suspects. You could do this on your word processor as well. Or, if you’ve been doing this a while, the work could go on in your head. The point is, churn out a lot of material before making any strict decisions. Then you’ll have all the more to work with and won’t get those constipated moments where you just can’t decide what to plot next.

Keep going back to your killer, victim, and sleuth when generating clues. Focus on the real clues. The red herrings can wait for now. Shuffle the clues around; think of where you’ll put them. If they’re suspects, figure out how and when you’re sleuth will meet them and what information they’ll get out of them. Also decide if your sleuth will recognize certain information as a clue right away. If not, when and how will the sleuth realize it is a clue?

Look at any subliminal plants you have. You’ve probably used a few already when working with your suspects. Again, ask yourself: where does this clue go, how does the sleuth encounter it, and when does he realize it’s a clue?

Remember cause and effect. One clue should lead to another.

With that in mind, bring out those red herrings. How and where will the sleuth uncover these? How will she interpret them (wrongly)? Can you use these red herrings to push the sleuth toward another clue or red herring?

See how this works?

In the special form of the mystery, you have to go beyond the simple scene-to-scene progression of a story. You have to go from clue to clue. What you should be doing now is imagining scenes where these clues are found and how they affect the storyline and where they place the sleuth in relation to the climax and revelation. If you think in terms of clues, suspects, and red herrings, you’ll simultaneously be plotting the novel. Pretty soon you’ll have the skeleton of your story, and you won’t have to worry, when it comes time to reveal the killer, that the evidence is there to back up your sleuth.

Other Plot Considerations

The core murder plot isn’t going to be your only plot. You’ll probably want to consider sub-plots. Perhaps a love interest for your sleuth, or maybe an internal struggle your sleuth must overcome. But that will all come a lot easier now that you have the mystery plotted. At this point you might even want to wing your subplots, improvising them as you go along. No matter what, you’ll know the mystery part (the really tricky part) of your story is solid and in place.

That’s the beauty of the mystery story. As long as you have that underlying plot structure, you can add whatever meat you want. In Crystal Past I have everything from the forming of a new friendship to the reconciliation of a son and mother, as well as my main character’s struggle against his own self-destructive nature, and his coming to terms with past mistakes.

The whodunit structure can hold all the themes and conflicts you want, while at the same time giving the reader a unique and moving experience in the shape of a tried and true story form.

So get a clue–get a whole bunch of them–and start plotting your mystery.

My best friend writing papers

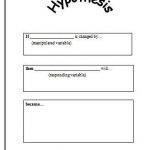

My best friend writing papers Writing a scientific hypothesis worksheet

Writing a scientific hypothesis worksheet Writing mysteries topics for children

Writing mysteries topics for children Khan academy sat writing tips

Khan academy sat writing tips London creative writing phd rankings

London creative writing phd rankings