What is an Abstract?

- The abstract is an important component of your thesis. Presented at the beginning of the thesis, it is likely the first substantive description of your work read by an external examiner. You should view it as an opportunity to set accurate expectations.

- The abstract is a summary of the whole thesis. It presents all the major elements of your work in a highly condensed form.

- An abstract often functions, together with the thesis title, as a stand-alone text. Abstracts appear, absent the full text of the thesis, in bibliographic indexes such as PsycInfo. They may also be presented in announcements of the thesis examination. Most readers who encounter your abstract in a bibliographic database or receive an email announcing your research presentation will never retrieve the full text or attend the presentation.

- An abstract is not merely an introduction in the sense of a preface, preamble, or advance organizer that prepares the reader for the thesis. In addition to that function, it must be capable of substituting for the whole thesis when there is insufficient time and space for the full text.

Size and Structure

- Currently, the maximum sizes for abstracts submitted to Canada’s National Archive are 150 words (Masters thesis) and 350 words (Doctoral dissertation).

- To preserve visual coherence, you may wish to limit the abstract for your doctoral dissertation to one double-spaced page, about 280 words.

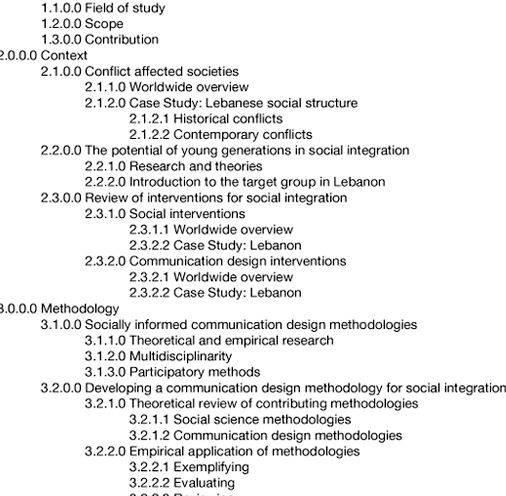

- The structure of the abstract should mirror the structure of the whole thesis, and should represent all its major elements.

- For example, if your thesis has five chapters (introduction, literature review, methodology, results, conclusion), there should be one or more sentences assigned to summarize each chapter.

- As in the thesis itself, your research questions are critical in ensuring that the abstract is coherent and logically structured. They form the skeleton to which other elements adhere.

- They should be presented near the beginning of the abstract.

- There is only room for one to three questions. If there are more than three major research questions in your thesis, you should consider restructuring them by reducing some to subsidiary status.

Don’t Forget the Results

- The most common error in abstracts is failure to present results.

- The primary function of your thesis (and by extension your abstract) is not to tell readers what you did, it is to tell them what you discovered. Other information, such as the account of your research methods, is needed mainly to back the claims you make about your results.

- Approximately the last half of the abstract should be dedicated to summarizing and interpreting your results.

by the FindAPhD Team.

What is a PhD proposal?

A PhD proposal is a an outline of your proposed project that is designed to:

- Define a clear question and approach to answering it

- Highlight its originality and/or significance

- Explain how it adds to, develops (or challenges) existing literature in the field

- Persuade potential supervisors and/or funders of the importance of the work, and why you are the right person to undertake it

Research proposals may vary in length, so it is important to check with the department(s) to which you are applying to check word limits and guidelines.

Generally speaking, a proposal should be around 3,000 words which you write as part of the application process.

What is the research proposal for?

Potential supervisors, admissions tutors and/or funders use research proposals to assess the quality and originality of your ideas, your skills in critical thinking and the feasibility of the research project. Please bear in mind that PhD programmes in the UK are designed to be completed in three years (full time) or six years (part time). Think very carefully about the scope of your research and be prepared to explain how you will complete it within this timeframe.

Research proposals are also used to assess your expertise in the area in which you want to conduct research, you knowledge of the existing literature (and how your project will enhance it). Moreover, they are used to assess and assign appropriate supervision teams. If you are interested in the work of a particular potential supervisor – and especially if you have discussed your work with this person – be sure to mention this in your proposal. We encourage you strongly to identify a prospective supervisor and get in touch with them to discuss your proposal informally BEFORE making a formal application, to ensure it is of mutual interest and to gain input on the design, scope and feasibility of your project. Remember, however, that it may not be possible to guarantee that you are supervised by a specific academic.

Crucially, it is also an opportunity for you to communicate your passion in the subject area and to make a persuasive argument about what your project can accomplish. Although the proposal should include an outline, it should also be approached as a persuasive essay – that is, as an opportunity to establish the attention of readers and convince them of the importance of your project.

Is the research proposal ‘set in stone’?

No. Good PhD proposals evolve as the work progresses. It is normal for students to refine their original proposal in light of detailed literature reviews, further consideration of research approaches and comments received from the supervisors (and other academic staff). It is useful to view your proposal as an initial outline rather than a summary of the ‘final product’.

Structuring a Research Proposal

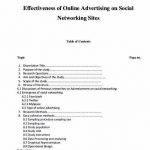

Please check carefully with each department to find out whether a specific template is provided or required. In general, however, the following elements are crucial in a good research proposal:

Title

This can change, but make sure to include important ‘key words’ that will relate your proposal to relevant potential supervisors, funding schemes and so on. Make sure that your title goes beyond simply describing the subject matter – it should give an indication of your approach or key questions.

Overview of the research

In this section you should provide a short overview of your research and where it fits within the existing academic discourses, debates or literature. Be as specific as possible in identifying influences or debates you wish to engage with, but try not to get lead astray into a long exegesis of specific sources. Rather, the point is to sketch out the context into which your work will fit.

You should also use this section to make links between your research and the existing strengths of the department to which you are applying. Visit appropriate websites to find out about existing research taking place in the department and how your project can complement this.

If applying to multiple departments, be sure to tailor a unique proposal to each department – readers can tell if a proposal has been produced for ‘mass consumption’!

Be sure to establish a solid and convincing framework for your research in this section. This should include:

- research questions (usually, 1-3 should suffice) and the reason for asking them

- the major approach(es) you will take (conceptual, theoretical, empirical and normative, as appropriate) and rationale

- significance of the research (in academic and, if appropriate, other fields)

Positioning of the research (approx. 900 words)

This section should discuss the texts which you believe are most important to the project, demonstrate your understanding of the research issues, and identify existing gaps (both theoretical and practical) that the research is intended to address. This section is intended to ‘sign-post’ and contextualize your research questions, not to provide a detailed analysis of existing debates.

Research design & methodology (approx. 900 words)

This section should lay out, in clear terms, the way in which you will structure your research and the specific methods you will use. Research design should include (but is not limited to):

- The parameters of the research (ie the definition of the subject matter)

- A discussion of the overall approach (e.g. is it solely theoretical, or does it involve primary/empirical research) and your rationale for adopting this approach

- Specific aims and objectives (e.g. ‘complete 20 interviews with members of group x’)

- A brief discussion of the timeline for achieving this

A well developed methodology section is crucial, particularly if you intend to conduct significant empirical research. Be sure to include specific techniques, not just your general approach. This should include: kinds of resources consulted; methods for collecting and analyzing data; specific techniques (ie statistical analysis; semi-structured interviewing; participant observation); and (brief) rationale for adopting these methods.

References

Your references should provide the reader with a good sense of your grasp on the literature and how you can contribute to it. Be sure to reference texts and resources that you think will play a large role in your analysis. Remember that this is not simply a bibliography listing ‘everything written on the subject’. Rather, it should show critical reflection in the selection of appropriate texts.

Possible pitfalls

Quite often, students who fit the minimum entrance criteria fail to be accepted as PhD candidates as a result of weaknesses in the research proposal. To avoid this, keep the following advice in mind:

- Make sure that your research idea, question or problem is very clearly stated, persuasive and addresses a demonstrable gap in the existing literature. Put time into formulating the questions- in the early stages of a project, they can be as important as the projected results.

- Make sure that you have researched the departments to which you are applying to ensure that there are staff interested in your subject area and available to supervise your project. As mentioned above it is strongly advised that you contact potential supervisors in advance, and provide them with a polished version of your proposal for comment.

- Make sure that your proposal is well structured. Poorly formed or rambling proposals indicate that the proposed project may suffer the same fate.

- Ensure that the scope of your project is reasonable, and remember that there are significant limits to the size and complexity of a project that can be completed and written up in three years. We will be assessing proposals not only for their intellectual ambition and significance, but also for the likelihood that the candidate can complete this project.

- Make sure that your passion for the subject matter shines through in the structure and arguments presented within your proposal. Remember that we may not be experts in your field it is up to you to make your project and subject matter engaging to your readers!

The following books are widely available from bookshops and libraries and may help in preparing your research proposal (as well as in doing your research degree):

Bell, J. (1999): Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-time Researchers in Education Social Science, (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

Baxter, L, Hughes, C. and Tight, M. (2001): How to Research, (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

Cryer, P. (2000): The Research Student’s Guide to Success, (Open University, Milton Keynes).

Delamont, S. Atkinson, P. and Parry, O. (1997): Supervising the PhD, (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

Philips, E. and Pugh, D. (2005): How to get a PhD: A Handbook for Students and their Supervisors. (Open University Press, Milton Keynes).

This article is the property of FindAPhD.com and may not be reproduced without permission.

Dissertation writing services singapore yahoo

Dissertation writing services singapore yahoo Phd dissertation sample topics for nursing

Phd dissertation sample topics for nursing Devoir de philosophie dissertation proposal

Devoir de philosophie dissertation proposal Dissertation writing services illegal golf

Dissertation writing services illegal golf Dissertation research proposal sample pdf

Dissertation research proposal sample pdf