In his Farewell Address, George Washington announced that he would leave the presidency after two terms. He spent the opening paragraphs justifying himself: “I beg you. to do me the justice to be assured that this resolution has not been taken without a strict regard to all the considerations appertaining to the relation which binds a dutiful citizen to his country.” Though he had led the nation to victory in its war for independence, come out of retirement to chair the Constitutional Convention, and come out of retirement again to serve as president, he nevertheless wanted the nation to know that he took his obligations as a citizen seriously.

In his address, he made clear that he expected his fellow citizens to do the same. “The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations,” he said. Writing not just for his generation but for ours, he warned us to frown “upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.”

It is worth asking how well we are meeting the test of civic virtue that Washington set for us. Do we have sufficient centripetal forces in our public life to maintain what he called “union and brotherly affection.”

While we celebrate national holidays, we tend to do so locally and often privately. Many, now changed to Mondays, seem to link us more to store sales and vacations than to our collective life.

Voting ought to serve this purpose, but half of us don’t vote. With the increasing trend toward mail and virtual voting, even the communal gathering at a polling place has morphed into a private exercise.

Military service used to be a great homogenizer of disparate Americans. It is now voluntary, thus depriving us of a mechanism that used to put us into contact with each other and give most Americans a reason to engage in civic conversation on the momentous decisions of war and peace.

Broadcast television, which provided a common experience when only three networks were available, has morphed into hundreds of cable and satellite channels which allow us to pick our news and views rather than forcing us to encounter those of people with whom we might disagree (and thus learn about and from). Presidents who once spoke to the nation from the Oval Office now rarely do so. Instead, they address friendly audiences against a backdrop of waving flags and wild applause, which only their already-partisan supporters watch.

Americans, who have always come together in times of national tragedy – whether it be a terrorist attack or a natural disaster – still do, but only briefly. But where are the ways to come together to take on national challenges or celebrate national successes? In 1969, we were bound together by landing men on the moon. Today, we seem bound together more by sensational criminal trials than by creative tests of our national talents and purpose.

Nowhere is the disaggregation of America more visible than in Congress, the institution that was designed to be the center of civic dialogue.

The Framers knew that strong passions would be aired there, but they counted on compromise. The nation’s needs would be served over factional interests. Yet Congress is populated with too many who seem more intent on hewing to the limited interests of gerrymandered and politically homogeneous electoral districts than to fostering “union and brotherly affection.”

In America, we honor the personal and the private. The issues that consume us in our national debates focus on rights demanded or protected – whether that be the right to life or choice, or the right to immigrate, to bear arms, to run a business as we wish, to marry who we want or to be protected against the ravages of old age. Obamacare, we should recall, was and is being sold far more on what it entitles each of us to get than on our communal responsibility to care for each other.

The Declaration of Independence is most often cited as a “rights” document. The purpose of government, we keep reminding ourselves, is to protect us in our individual capacities. Yet that purpose cannot be served unless there is a good government, unless we perform our civic duty to each other. That is what Washington meant when he said in his address, that “The unity of government which constitutes you one people is. a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very liberty which you so highly prize.” The Declaration, we should also recall, is a “responsibilities” document as well. Thirteen diverse colonies took on the communal task of defeating the greatest military power in the world – and its signers pledged to each other their “lives, fortunes, and sacred honor.”

Civic virtue is much healthier at the local and state level than at the national level these days, and in the many non-governmental yet public efforts in which Americans regularly and enthusiastically involve themselves and help each other. But that was not enough for Washington, nor should it be enough for us. Our system of government, and hence our liberty, he argued, depend on all parts of our government having the emotional and practical support of the people – and the people being bound, as he put it, by “sympathy and interest” with each other.

Polls suggest that Americans understand the need to foster national civic virtue as well as celebrate individual rights. Nearly sixty percent support a program of national military or public/community service for people aged 18-24. President Obama recently charged federal agencies with improving national service and volunteering. What we need are many more people – and leaders – willing to echo Washington. As he also said in his Farewell Address, “the independence and liberty you possess are the work of joint counsels, and joint efforts of common dangers, sufferings, and successes.” When we have more joint counsels and efforts, we shall have more civic virtue. We will have met the test of not only securing our rights but living up to our responsibilities.

More:

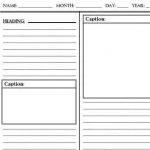

Writing a news article esl worksheet

Writing a news article esl worksheet Jrr tolkien online article writing

Jrr tolkien online article writing Article writing companies in bangalore

Article writing companies in bangalore Article 8 cedh dissertation proposal

Article 8 cedh dissertation proposal Writing newspaper articles ppt file

Writing newspaper articles ppt file