Subject sentences and signposts make an essay’s claims obvious to some readers. Good essays contain both. Subject sentences reveal the primary reason for a paragraph. They reveal the connection of every paragraph towards the essay’s thesis, telegraph the purpose of a paragraph, and inform your readers what to anticipate within the paragraph that follows. Subject sentences also establish their relevance immediately, making obvious why what exactly they are making are essential towards the essay’s primary ideas. They argue instead of report. Signposts. his or her name suggests, prepare the readers for something new within the argument’s direction. They reveal what lengths the essay’s argument has progressed vis–vis the claims from the thesis.

Subject sentences and signposts occupy a middle ground within the writing process. They’re neither the very first factor a author must address (thesis and also the broad strokes of the essay’s structure are) nor could they be the final (that’s by visiting to sentence-level editing and polishing). Subject sentences and signposts deliver an essay’s structure and intending to a readers, so that they are helpful diagnostic tools towards the writer—they tell you if your thesis is arguable—and essential guides towards the readers

Types of Subject Sentences

Sometimes subject sentences are really two or perhaps three sentences lengthy. When the first constitutes a claim, the 2nd might think about claiming, explaining it further. Consider these sentences as asking and answering two critical questions: So how exactly does the phenomenon you are discussing operate? How come it operate because it does?

There is no set formula for writing a subject sentence. Rather, you need to try to vary the shape your subject sentences take. Repeated too frequently, any method grows boring.

Listed here are a couple of approaches.

Complex sentences. Subject sentences at the outset of a paragraph frequently match a transition in the previous paragraph. This can be made by writing a sentence which contains both subordinate and independent clauses, as with the instance below.

Although Youthful Lady having a Water Pitcher depicts a mystery, middle-class lady in an ordinary task, the look is much more than “realistic” the painter [Vermeer] has enforced their own order on there to bolster it.

This sentence employs a helpful principle of transitions: always change from old to new information. The subordinate clause (from “although” to “task”) recaps information from previous sentences the independent clauses (beginning with “the lookInch and “the painter”) introduce the brand new information—a claim about how exactly the look works (“greater than realistic'”) and why it really works because it does (Vermeer “strengthens” the look by “imposing order”).

Questions. Questions, sometimes in pairs, also make good subject sentences (and signposts). Think about the following: “Will the commitment of stability justify this constant hierarchy?” We might fairly think that the paragraph or section that follows will answer the issue. Questions are obviously a kind of inquiry, and therefore demand a solution. Good essays shoot for this forward momentum.

Bridge sentences. Like questions, “bridge sentences” (the word is John Trimble’s) make a great replacement for more formal subject sentences. Bridge sentences indicate both what came before and just what comes next (they “bridge” sentences) with no formal trappings of multiple clauses: “But there’s an idea for this puzzle.”

Pivots. Subject sentences don’t always appear at the outset of a paragraph. When they are available in the center, they indicate the paragraph can change direction, or “pivot.” This tactic is especially helpful for coping with counter-evidence: a paragraph begins conceding a place or stating a well known fact (“Psychiatrist Sharon Hymer uses the word narcissistic friendship’ to explain the first stage of the friendship such as the one between Celie and Shug”) after following on this initial statement with evidence, after that it reverses direction and establishes claims (“Yet. this narcissistic stage of Celie and Shug’s relationship is just a temporary one. Hymer herself concedes. “). The pivot always requires a signal, a thing like “but,” “yet,” or “however,” or perhaps a longer phrase or sentence that signifies an about-face. It frequently needs several sentence to create its point.

Signposts operate as subject sentences for whole sections within an essay. (In longer essays, sections frequently contain greater than a single paragraph.) They inform a readers the essay takes a submit its argument: delving right into a related subject like a counter-argument, walking up its claims having a complication, or pausing to provide essential historic or scholarly background. Simply because they reveal the architecture from the essay itself, signposts help remind readers of the items the essay’s stakes are: how it is about, and why it’s being written.

Signposting can be achieved inside a sentence or two at the outset of a paragraph or perhaps in whole sentences that provide as transitions between one area of the argument and subsequently. The next example originates from an essay analyzing the way a painting by Monet, The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of the Train, challenges Zola’s declarations about Impressionist art. A student author wonders whether Monet’s Impressionism can be as dedicated to staying away from “ideas” in support of direct sense impressions as Zola’s claims would appear to point out. This is actually the start of essay’s third section:

It’s apparent within this painting that Monet found his Gare Saint-Lazare motif fascinating at most fundamental degree of the play of sunshine along with the loftiest degree of social relevance. Arrival of the Train explores both extremes of expression. In the fundamental extreme, Monet satisfies the Impressionist purpose of recording the entire-spectrum results of light on the scene.

The author signposts this within the first sentence, reminding readers from the stakes from the essay itself using the synchronised references to sense impression (“play of sunshineInch) and intellectual content (“social relevance”). The 2nd sentence follows on this concept, as the third works as a subject sentence for that paragraph. The paragraph next commences with a subject sentence concerning the “cultural message” from the painting, something which the signposting sentence predicts by not just reminding readers from the essay’s stakes but additionally, and quite clearly, indicating exactly what the section itself contains.

2000, Elizabeth Abrams, for that Writing Center at Harvard College

Writing greek myths ks2 past

Writing greek myths ks2 past Improve your ielts writing skills online

Improve your ielts writing skills online Phd creative critical writing tips

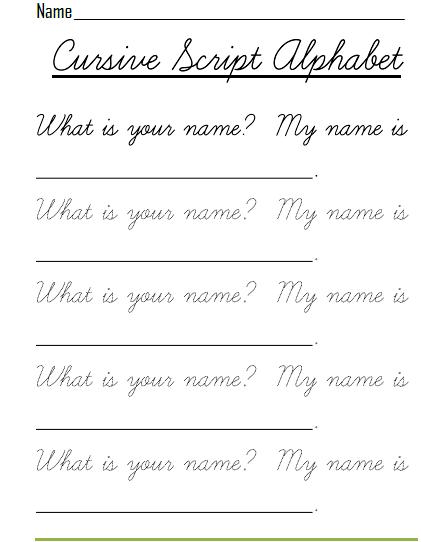

Phd creative critical writing tips Practice writing your name in cursive

Practice writing your name in cursive Letter writing for and on behalf of my family

Letter writing for and on behalf of my family