I. What an Academic Essay Needs to Do

1. An academic essay attempts to address an intellectual problem or question. The first rule, therefore, of successful essay writing is making sure you are actually writing an essay on the topic or question your instructor has set before you, rather than some other, random question.

2. Beyond this, an essay is analytical rather than descriptive. It is not enough to describe what happened or to write a narrative of past events. You must argue a position.

3. Essays also attempt to persuade. Having posed a question or problem in the first paragraph of your essay, and having stated your thesis, you then need to convince your reader of the validity of your position. In order to persuade, you need to argue in a logical fashion.

a. To do this, you should first write an outline before you begin to draft your essay. An outline will help you organize your argument, and it will, in the end, produce a more cogently argued paper.

b. Second, you should include only the information in your essay that is relevant to the question you are addressing. Other information, whether factually correct or not, is irrelevant. It confuses your reader and obscures the point you are trying to argue.

c. Third, your essay should take your reader by the hand (so to speak) and guide him or her through the process of thought leading to the conclusions you want your reader to draw. You should assume that your reader is intelligent but does not necessarily know the material you are presenting. Thus, if certain facts are critical to an essay, you must present them as such, and you cannot assume that the reader already knows them.

d. Fourth, to convince your reader that your thesis is correct, you must support your point of view with evidence.

Use quotations and examples from your readings and from lectures to prove your points.

4. You must, however, consider all evidence, even the evidence which might, at first glance, seem to disprove your argument: you must explain why awkward or contradictory evidence does not, in fact, undermine your conclusions. If you cannot provide such an explanation, then you must modify your thesis. It is never acceptable to avoid unpleasant evidence by simply ignoring it.

II. Basic Structure

1. An essay must have an introductory paragraph that lets your reader know what your thesis is and what the main points of your argument will be. An essay must also have a conclusion (at least a paragraph in length) that sums up its most important arguments. In short, over the course of your essay, you must tell readers what you are going to say, say it, and then tell them what you have said.

2. Paragraphs are the building blocks of an essay. Each paragraph should contain a single general idea or topic, along with accompanying explanations and evidence relevant to it. Each paragraph, moreover, has a topic sentence (usually the first sentence) that tells the reader what the paragraph is about.

3. Do not write one-, two-, or three-sentence paragraphs. Paragraphs have topics, introductory sentences, evidence, and conclusions.

4. Do not write two- or three-page paragraphs. A paragraph generally explores a single idea, rather than a dozen.

5. Before you end a discussion of one major topic and begin another, it is important to summarize your findings and analyze their importance for your thesis.

It is also necessary to write a transition to alert your reader that you have begun a new topic. Thus, if your thesis is hinged on three major points, you should spend a couple of pages on each point and write a transition paragraph between each section.

III. Formal Written English

1. Avoid colloquialisms (e.g. cool. kind of. totally. hung up on. OK. sort of. etc.). They are fine in speech, but they should never be used in formal written English.

2. On the other hand, do not use antiquated or obscure words that have been suggested to you by your computer’s thesaurus, especially if you are not sure what these words mean.

3. Avoid contractions (e.g. don’t. can’t ) in a formal written piece of work.

4. Gender-inclusive language should be used, but it should be used sensibly. On the one hand, if you mean all people living in society, do not describe them with the word men. On the other hand, if gender-inclusive language makes what you are saying incorrect, do not use it. In other words, when speaking about monks (who are men), do not say he or she. If talking about the right to vote in the nineteenth century, the same principle holds, as women could not then vote.

5. It is all right to use I. me. or my now and again, but do not overuse them. It is unnecessary to use expressions such as in my opinion. as your reader will assume that whatever you write in your paper that is not attributed to another author is your opinion.

6. Do not use the general you. Use one instead.

7. When you first discuss an author or historical figure, use first and last name. After this, you are free to use last name only. Do not, however, refer to historical figures by their first name; e.g. Karl Marx should be referred to as Marx. rather than Karl. This rule applies for women as well as men. Emily Dickinson should be called Dickinson rather than Mrs. Dickinson .

8. Avoid beginning sentences and paragraphs with the word however. and never end a sentence with however .

9. However can be used only to link two halves of a single sentence, separated by a semicolon (not a comma), if both clauses have something to do with one another. Incorrect: He was hungry; however, it was a warm day.

10. The words while and although have slightly different meanings. Although means regardless of the fact that or even though. While means at the same time that.

IV. Verbs

1. Stick to the past tense as much as possible. Do not write about long-past events and long-dead people in the present tense.

2. Do not, however, change the tense of verbs in passages you are quoting.

3. Think carefully when you use the passive voice in favor of the active voice. Luther believed that… is better, clearer, and punchier than It was believed by Luther that…. and A.G. Bell invented the telephone is better than The telephone was invented by A.G. Bell. because Luther and Bell were acting rather than being acted upon. Still, people are acted upon as well as act, and events are caused as well as happen on their own accord. When you are attempting to express this, by all means use the passive voice (e.g. Smith had been unemployed during the Depression. or Peasants had been removed from their lands during Enclosure ).

V. Nouns and Adjectives

1. Write out numerals (except dates) under 100 (i.e. three instead of 3 ), except when they appear as the first word of a sentence or are being used as percentages.

2. Do not use an apostrophe for decades (i.e. 1920s. not 1920’s ).

3. Write out all centuries (i.e. sixteenth century. not 16th century ).

4. When a century is used as an adjective — that is, as a phrase that describes a noun (i.e. sixteenth-century art ) — it is hyphenated. When a specific century is used as a noun (i.e. at the end of the sixteenth century ) it is not hyphenated.

5. You also must hyphenate other pairs of words when using them as adjectives. For example, when African American is used as a noun (African Americans were long denied the right to serve on juries ), there is no hyphen. When it is used as an adjective (African-American men are often stopped without cause by the police ) there is a hyphen. The same rule applies to middle class. working class. or any other pair of words. When pairs of words act like nouns, they are not hyphenated; when they act like adjectives, they are.

6. Adjectives make for interesting writing, but they should be used sparingly. The Communist Manifesto was really, truly very much a work of ground-breaking importance is not as good as The Communist Manifesto was ground breaking .

7. In most cases, it is wise to avoid using the same word twice in a single sentence or many times in a single paragraph.

8. Nonetheless, some ideas, institutions, and activities have highly technical meanings, and synonyms cannot be found for them. A communist. for example, should not be called a socialist. nor should slavery be termed vassalage. indenture. or some other word that does not actually mean slavery. Just because these synonyms have been suggested by your computer’s thesaurus does not mean your computer knows what it is talking about. You need to think carefully about the meaning of the words you use.

9. Avoid using anachronistic terms. Words like superstition , the masses. the people. nation. citizens. and countries can all be used to describe the modern world, but they are inappropriate for the pre-Modern period. For example, just as you would not describe twentieth-century France as a kingdom. you should not describe twelfth-century France as a nation .

10. Make sure that single nouns match single pronouns and verbs, and that plural nouns match plural pronouns and verbs. Consider these sentences: The conventions connected them to a national body of women who shared ideals and beliefs. It allowed them to work with black men. In this sentence, they should have been used instead of it. Another example: His first memories of slavery was… The word was should be were .

11. Make sure that the antecedents of your pronouns (i.e. the nouns to which pronouns refer) are correct. Read the following sentence: Masters tried to use religion to control slaves, but they were not very interested in conversion. The author is trying to say that masters were not concerned with the spiritual conversions of their slaves. Grammatically, however, the word they refers to slaves rather than masters. because the noun slaves is closer to the pronoun they than the noun masters. This makes the sentence factually incorrect, since slaves were very interested in their own spiritual lives.

12. Avoid using this or that as a subject (i.e. This made an enormous difference ). It is better to be more specific: (i.e. This new development made an enormous difference ).

VI. Quotations

1. Quoted material needs to be introduced. You cannot simply throw in a quotation without introducing it in a way that allows your reader to see what it is doing there (i.e. This is clearly the case when Smith writes… or For example, Athanasius argued that… )

2. Examples or quotations should not, however, be introduced as follows: On page five it says… or In the book it says…

3. Indent and single-space long quotations (generally anything more than three lines). When you have indented a quotation, do not use quotation marks. The indentation, itself, marks this as a quotation.

4. Check all quotations carefully against the text. The price of using someone else’s words to prove your point is quoting them accurately!

VII. Punctuation and Capitalization

1. However and therefore are almost always preceded by a comma or semicolon and followed by a comma (i.e. …, however,… ).

2. Which is more often than not preceded by a comma (i.e. …,which… ).

3. If you have written a two-part sentence joined by an and. and if both parts can stand on their own as sentences, the and should be preceded by a comma. Thus, Henry II´s justiciars traveled to shire courts, and they gave judgments there ; but: Henry II’s justiciars traveled to shire courts and gave judgments there. The second sentence does not take a comma, because the last clause cannot stand on its own as a sentence.

4. All punctuation marks go inside quotation marks. (Correct: like this. Incorrect: like this .)

5. Avoid exclamation points.

6. There is a difference between a hyphen (-) and an em dash (—). A hyphen joins two words, usually those in an adjectival phrase. An em dash represents a break in thought or a pause for emphasis; it is usually typed as two hyphens. For example: Nineteenth-century France experienced several different kinds of governments — three republics, two empires, and two monarchies. The character between Nineteenth and century is a hyphen. The character between governments and three is an em dash.

7. Either underline or italicize all book titles and foreign words.

8. Titles such as king, bishop, senator, and prime minister, when attached to a personal name, should be capitalized (e.g. Saint Martin. Senator Kennedy ). They should not, however, be capitalized if they are used as nouns unattached to personal names (e.g. According to Gregory, all bishops… ).

9. Your papers are written in English, not German. Unlike German, English does not capitalize nouns as a matter of course. Do not capitalize nineteenth century. lords. law. jurors. legal reform. slavery. working class. capitalism. socialism. etc. Words are not capitalized simply because they represent something important. The rule is: When in doubt, do not use capitals.

VIII. Footnotes and Bibliographies

Instructors may give you very specific instructions about footnote and bibliography styles. The websites for Hacker and Fister’s Research and Documentation in the Electronic Age and The Columbia Guide to Online Style contain basic information about the most common footnote and bibliography formats, including Turabian, MLA, and APA.

IX. Finishing Touches

1. Always number the pages of your paper.

2. Always double-space your papers, use a ten- or twelve-point font, and stick to the standard margins set by your word-processing program.

3. Papers should be stapled. Paper clips, plastic clips, and ornamental binders should not be used.

4. Never turn in a paper without running it through your spell-check program. Remember, however, that spell-check programs do not catch everything. If you have misspelled a word in context, but this misspelling is, itself, a word (e.g. if for is. or their for there ), spell check will not catch your mistake. Do not rely on grammar check to catch these errors, either.

5. Always reread your paper carefully before you print out a final draft. Make sure that every sentence makes sense, that words have not accidentally dropped out of your text when you made corrections to it, or that your spell-check program has not introduced errors (e.g. salve for slave. Santa for Satan. Richard Nikon for Richard Nixon. etc.). If you read your paper out loud, you are more likely to catch mistakes than if you read it silently.

X. Academic Integrity

It is your responsibility to follow University rules and regulations in regards to matters of academic integrity. If you do not have a clear idea about what constitutes plagiarism or cheating, or what activities, when writing a paper, are considered violations of University policy, it is your responsibility to find out. For further information, visit the University Policies page on the Student Services web site.

XI. A Final Word:

1. Writing does not depend on the possession of a muse. Instead, it is just plain, hard work. The more work you put into your essay, the better it will be. This means that the earlier you begin to start collecting information relevant to your paper and the sooner you begin thinking in general ways about the topic, the better your essay will be.

2. Second drafts are always better than first drafts, and third drafts are better than second drafts. Therefore, always rewrite your paper before you give it to your instructor.

Evaluate the essay question. The first thing to do if you have a history essay to write, is to really spend some time evaluating the question you are being asked. No matter how well-written, well-argued, or well-evidenced your essay is, if you don’t answer the answer the question you have been asked, you cannot expect to receive a top mark. Think about the specific key words and phrasing used in the question, and if you are uncertain of any of the terms, look them up and define them. [1]

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2]

- For example, if the question was “To what extent was the First World War a Total War?”, the key terms are “First World War”, and “Total War”.

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don’t waste time.

Can you please put wikiHow on the whitelist for your ad blocker? wikiHow relies on ad money to give you our free how-to guides. Learn how .

Consider what the question is asking you. With a history essay there are a number of different types of question you might be asked, which will require different responses from you. You need to get this clear in the early stages so you can prepare your essay in the best way. Look at your set essay question and ask yourself whether you are being asked to explain, interpret, evaluate, or argue. You might be asked to do any number or all of these different things in the essay, so think about how you can do the following:

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn’t happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3]

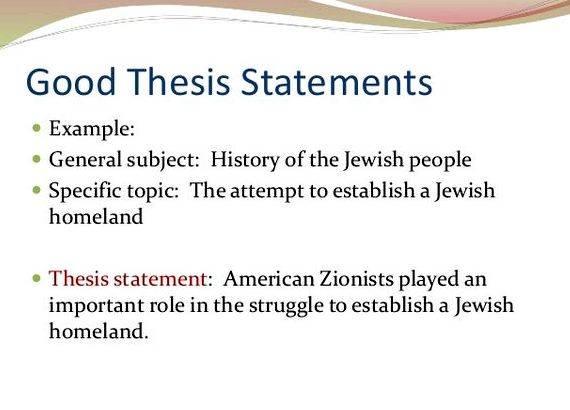

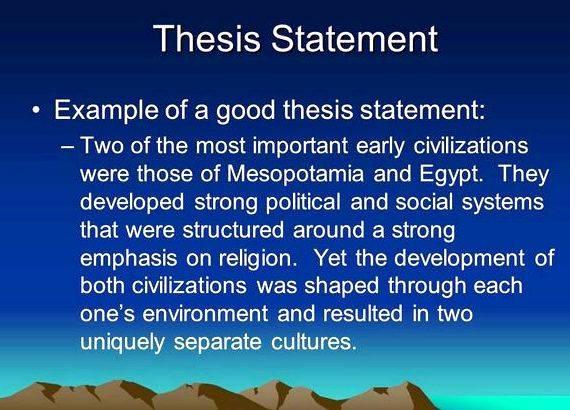

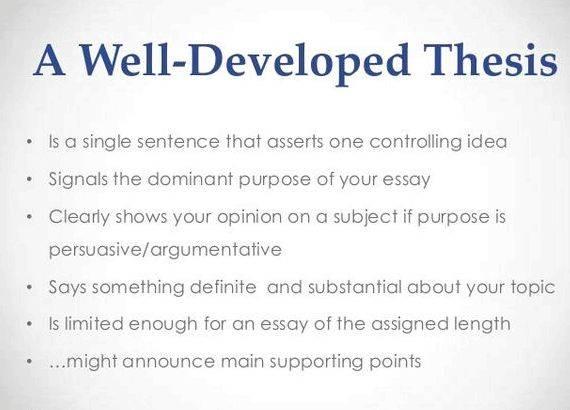

Try to summarise your key argument. Once you have done some research you will be beginning to formulate your argument, or thesis statement, in your head. It’s essential to have a strong argument which you will then build your essay around. So before you start to plan and draft your essay, try to summarise your key argument in one or two sentences.

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- The main point of your essay should be clear enough that you can structure the essay plan around it. [4]

- For example, your summary could be something like “The First World War was a ‘total war’ because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front”.

Make an essay plan . Once you have evaluated the question, you need to draw up an essay plan. This is a great opportunity to organise your notes and start developing the structure which you will use for your essay. When drawing up the plan you can assess the quality and depth of the evidence you have gathered and consider whether your thesis statement is adequately supported.

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5]

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Part Two of Five:

Doing Your Research Edit

Distinguish between primary and secondary sources. A history essay will require a strong argument that is backed up by solid evidence. The two main types of evidence you can draw on are known as primary and secondary sources. Depending on the essay you are writing, you might be expected to include both of these. If you are uncertain about what is expected be sure to ask your teacher well in advance of the essay due date.

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography. [6]

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

Find your sources. It can be difficult to get going with your research. There may be an enormous number of texts which makes it hard to know where to start, or maybe you are really struggling to find relevant material. In either case, there are some tried and tested ways to find reliable source material for your essay.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources. [7]

- Don’t go straight to an internet search engine. If you are tempted to just type your topic into the search bar, you will find lots of results, but the scholarly value will be questionable and you will have to spend a lot of time wading through sites before you find the good sources.

Evaluate your secondary sources. It’s very important that you critically evaluate your sources. For a strong academic essay you should be using and engaging with scholarly material that is of a demonstrable quality. It’s very easy to find information on the internet, or in popular histories, but you should be using academic texts by historians. If you are early on in your studies you might not be sure how to identify scholarly sources, so when you find a text ask yourself the following questions:

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it’s an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8]

Read critically. Once you found some good sources, you need to take good notes and read the texts critically. Try not to let your mind drift along as you read a book or article, instead keep asking questions about what you are reading. Think about what exactly the author is saying, and how well the argument is supported by the evidence.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn’t match the author’s claims. [9]

Take thorough notes. When you are taking notes you should be wary of writing incomplete notes or misquoting a text. It’s better to write down more in your notes than you think you will need than not have enough and find yourself frantically looking back through a book.

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can’t remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don’t reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10]

Have a clear structure. When you come to write the body of the essay it is important that you have a clear structure to your argument and to your prose. If your essay drifts, loses focus, or becomes a narrative of events then you will find your grade dropping. Your introduction can help guide you if you have given a clear indication of the structure of your essay. [15]

Develop your argument. The body of the essay is where your argument is really made and where you will be using evidence directly. Think carefully about how you construct your paragraphs, and think of each paragraph as one micro-sized version of the essay structure. In other words, aim to have a topic sentence introducing each paragraph, followed by the main portion of the paragraph where you explain yourself and draw on the relevant evidence. [16]

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don’t forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

Use source material appropriately. How you use your evidence will play a large part in how convincing your argument is and how well your essay reads. You can introduce evidence by directly quoting it, or by summarising it. Using evidence strategically and intelligently will seriously improve your essay. Try to avoid long quotations, and use only the quotes that best illustrate your point. [17]

- Don’t drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully reference anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

Make your essay flow. The fluency of your text is an important element in the writing a good history essay that can often be overlooked. Think carefully about how you transition from one paragraph to the next and try to link your points together, building your argument as you go. It is easy to end up with an essay that reads as a more or less disconnected series of points, rather than a fully developed and connected argument.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: “Additionally”, “Moreover”, “Furthermore”.

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [18]

Conclude succinctly. A good conclusion should precisely and succinctly summarise your argument and key points. You need to make sure your conclusion reflects the content of your essay, and refers back to the outline you provided in the introduction. If you read your conclusion and it doesn’t directly answer the essay question you need to think again.

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it’s significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [19]

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Music research paper thesis proposal

Music research paper thesis proposal Online editing services writing paper

Online editing services writing paper Writing high school thesis paper

Writing high school thesis paper My dream holiday writing paper

My dream holiday writing paper American history research paper thesis proposal

American history research paper thesis proposal