by Joshua Jenkins

Joshua Jenkins is a special education teacher at New Orleans College Prep Charter School. He is a Teach For America corps member.

As a special education teacher who teaches struggling readers with different disabilities, I’m often crafting mental lists of things I wish parents knew about their struggling readers and students with learning disabilities, not out of frustration or defense, but out of an earnest desire to see increased confidence and results from my students. Most important, I am eager for the parents of my students to understand that their children can and will learn to read, that their children have strengths, not just weaknesses. I want parents to know how preparing their children to learn to deal with their disability can inspire confidence and enable them to look forward to a proud future where they understand their disability as well as their strengths, self-advocating for their unique learning style. This is my manifesto for the struggling reader.

1. Notice Your Child’s Success

“My baby can’t read!” a mother shouts in front of her child and her teachers. Your child has strengths. Maybe he can draw beautifully or has an amazing vocabulary. Maybe she has great listening skills.

Often, I feel like my students’ parents are so consumed by their kids’ deficits in reading that they forget the things their children can do well. (Teachers are guilty of this, too.) If your child is artistic, use that talent at home as a way for your child to show understanding of a story you read aloud; draw a picture of the problem in the story, or draw the main character. Just because your child can’t physically decode the words and/or write a response to a reading comprehension question doesn’t mean you can’t push for higher oral comprehension, or neglect one of your child’s strengths.

Letting your children use their strengths will boost their confidence, and it has the benefit of letting them see that you know they are excelling at something.

2. Celebrate Every Success

“Mom, can we get ice cream?” “NO! Not with those grades on that report card,” says a disappointed parent.

Celebrate every success with a good job or a high five. Every single one. Don’t rely on report card grades to be the judge of your student’s progress. Celebrate his or her reading a singular word correctly. Meet your child on his/her reading level and celebrate the successes at that level. If your child is a beginning or practically a non-reader, celebrate decoding the word “at” or using a picture to solve an unknown word. If your child is beginning to read more fluently, celebrate when they self-correct an error. In my daily small group reading class, I find myself giving praise constantlyand it’s because I want them to know that I notice their progress and the things they do well. If what we’re reading is challenging, a smile and a “good job” can turn the whole lesson around. When I hear parents of my kids fussing at them about grades, I immediately find myself telling the parent about a smallbut wonderfulsuccess his/her child had reading or writing that school day. Harassing the students over report card grades isn’t going to boost their confidence.

Struggling readers need to know what they’re doing right, not just their mistakes.

3. Be Honest with Yourself: Set Realistic Goals

“I want my baby to get on-level.”

Saying you want your baby to read on-grade level will not happen overnight. I’m sorry to say it so bluntly, but you need to be honest with yourself and your student about your child’s progress.

Set goals. An easy way to make the very, very long road (did I mention it’s long?) to becoming an on-level reader is to set some very short-term concrete goals. As a teacher who uses a reading-assessment system and leveled books, my goals for students are often their successfully moving up a single reading level. At home, you might set a goal even to just practice reading every day. For example, you might suggest that your child read a certain number of leveled, independent books in a month (leveled books are books that your child can read independently or with only a little help), or you might set a goal of reading an interesting chapter book with your child. Make a countdown and cross out each book or chapter, respectively, until you reach your goal. Remember: you’re setting a goal that is achievable for you and your student that will positively affect his/her reading. (Reading those independent, leveled books at home or hearing that chapter book is a lot of great reading and listening practice that I wish more of my students did at home.) What the goal really does is allow them to see that they’re capable of reaching a goal, that they can be successful. You’re giving them a chance to develop another strength.

4. Don’t Let Poor Spelling Stop Your Child

“He fails every spelling test. He can’t spell anything!”

I hear this from nearly every parent of my students with learning disabilities. If your child has a learning disability, there is a real possibility that he may really struggle with spelling and remembering even very basic word patterns. Here’s the secret: that’s okay. Teach your child to cope. Even if your children can’t spell, they still have ideas that they need to express. Don’t let poor spelling make your child mute. Use a dictionary, spell check, or text-prediction software. Have your child start their very own personal word dictionary as a tool to use while they write. Talk to your student’s teacher. See what technology or other strategies there might be to help your child become more successful. There’s a lot out therebut you won’t find much if you’re too busy pointing out that your kid can’t spell.

5. Share Your Own Difficulties with Your Kids

“My child doesn’t want to read at home.”

Here’s why your child does not want to read at home: when something is difficult and doesn’t come easy, you generally just flat out don’t want to do it! What makes struggling readers even more anxious about reading is the pressure they’re getting both at school and at home to learn to read. (This is yet another reason why setting goals and celebrating every small success are so important.) Tell your child the things you’re not great at. Admitting that you also have things you struggle with can provide support and help your struggling reader understand that people have different strengths and weaknesses. An anecdote I often share with my frustrated readers is how I have always had terrible hand-to-eye coordination. And as an adult, I even maintain a joke with the people I interact with regularly: “do not throw anything to me or expect me to throw something to you.” That’s right; I am terrible at nearly every sport. However, I’ll always give it a shot, and I try. When I’m on family vacation and it’s time for some beach volleyball, you’ll find me flailing beside the net or nose-diving into the sand. (This is the moral, the part where you’re supposed to understand why I’m rambling about my lack of athleticism. Kids should try things they’re not great at, and they should know you have weaknesses, too. )

6. Read Aloud to Your Child–It’s Fun and Helpful

“My kid doesn’t understand what he reads!”

Your struggling reader can do moreif you help. Struggling readers should be read to every single day. Hearing someone else read not only helps your students hear the language they speak, it also has the amazing possibility of sparking creativity and interest and a chance to work on comprehension without the battle of decoding the text. A struggling reader may only read short, short books with little interest or depth, or because, if reading is a challenge, they may not fully understand the content of the text. When you read aloud (or have a program such as an iPad app that reads books aloudcall it old-fashioned, but a real human reading to children is better), they have the opportunity to focus on the meaning of the words. They develop background knowledge, culture, and it allows them to use their imagination.

7. Kids Feel Supported When They See Parents and Teachers Working Together to Help Them

“Honey, Mom and Dad are talking to the teacher right now. Go play with that puzzle over there.”

I cringe at any parent-teacher meeting where I hear those words. Your child’s education is not a private matter that excludes your child. It’s the child’s education! He or she needs to know what’s going on, and it hurts your child’s confidence when you tell him to go somewhere else while you and the teacher tell each other secrets. Do your kids a favor and tell them where they stand academically, what their talents are, what they need help with, and the plan for helping them learn. Remember: you, the parents, will have a plan and a goal in mind! Also remember that your child’s teacher will have a plan as well. Kids feel supported when they see parents and teachers working together to help them, but not when they are shuffled off into a corner to do the proverbial puzzle.

8. Small Steps Can Bring Big Improvements

“What can I do at night with my daughter (or son)”

This list could go on and on, but there is one more important thing to remember. It doesn’t need to be complicated. If your child is just beginning to read or is a very slow reader, go over the alphabet and letter sounds. Break apart short CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words (sit, hat, log, and so on), and blend these sounds together (/j/ /o/ /b/; job). If your child is a little more independent, sit with her, help her with hard words as she reads, maybe read aloud a chapter of a fun book to her every night before bed. Talk about what happened in the story, the characters, and the setting; what’s the problem in the story? Read a nonfiction book and talk about what you all learned from the text.

If your struggling child is older, let her be the teacher and read her books to siblings. Or, in our tech-obsessed culture, teach your child to grab a camera or recorder and record videos or audio notes of herself reading and then follow along with them, checking errors in reading.

9. It’s Okay to Read Slowly

“My kid reads so slowly.”

This is all right. Struggling readers and students with learning disabilities may read slowly. They might read faster as they grow in their reading ability or, like nearly all dyslexics, they may be a slow reader for life. If your child is reading below a mid-second grade level, don’t worry about fluency or speed. Focus on accuracy, or reading the words correctly. And if your child is diagnosed with dyslexia, don’t pressure him to read faster. Instead, give him strategies to help him remember what he read, such as writing a sentence or two or drawing a picture of what happened on each page (or in each chapter). Your kid is going to live with a learning disability as an adult. Teach him how to deal with it now, so he’ll be better able to navigate the world later.

10. Teach Them How to Help Themselves

“Will my child grow out of this?”

If your child has been diagnosed with a learning disability, no. But that doesn’t mean your child won’t learn how to read or be a complete failure. If you teach your child how to cope and deal with his/her disability now, you’re doing your child an incredible favor. Teach your children to advocate for themselves. Teach them how to ask for help. Teach them how to understand their strengths and weaknesses. Teach them about resources they can go to for help and how to ensure they receive the accommodations they need for success. If you teach your children to do this at school, they’re going to go into the world feeling confident and set up for success; they’ll know how they fit in and what they need to do to keep up. And that’s worth more than being able to read 180 words per minute.

Myakka skunk ape letter writing

Myakka skunk ape letter writing Egyptian scribes writing greek myth

Egyptian scribes writing greek myth Particle at the end of the universe summary writing

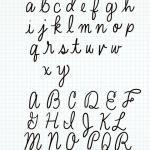

Particle at the end of the universe summary writing My photo in different styles of writing

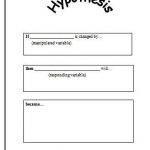

My photo in different styles of writing Writing a good hypothesis worksheet middle school

Writing a good hypothesis worksheet middle school