Our consultants assist students to focus on a specific gap in the knowledge and meet

the requirements in this chapter needed to defend the choice of that gap.

Chapter 1, with a highly focused review of the literature, and is normally the “prospectus” that a committee approves before the “proposal” to start research is approved. After the prospectus is approved, some of the review of literature may be moved into Chapter 2, which then becomes part of the proposal to do research.

Chapter 1 is the engine that drives the rest of the document, and it must be a complete empirical argument as is found in courts of law. It should be filled with proofs throughout. It is not a creative writing project in a creative writing class; hence, once a word or phrase is established in Chapter 1, use the same word or phrase throughout the dissertation. The content is normally stylized into five chapters, repetitive in some sections from dissertation to dissertation. A lengthy dissertation may have more than five chapters, but regardless, most universities limit the total number of pages to 350 due to microfilming and binding considerations in libraries in those institutions requiring hard copies.

Use plenty of transitional words and sentences from one section to another, as well as subheadings, which allow the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought. Following is an outline of the content of the empirical argument of Chapter 1. Universities often arrange the content in a different order, but the subject matter is the same in all dissertations because it is an empirical “opening statement” as might be found in a court of law. (Note that a dissertation could also be five pages of text and 50 pages of pictures of dragonfly wings and qualify for a Doctor’s degree in entomology.)

State the general field of interest in one or two paragraphs, and end with a sentence that states what study will accomplish. Do not keep the reader waiting to find out the precise subject of the dissertation.

Background of the Problem

This section is critically important as it must contain some mention of all the subject matter in the following Chapter 2 Review of the Literature 2 and the methodology in Chapter 3. Key words should abound that will subsequently be used again in Chapter 2. The section is a brief two to four page summary of the major findings in the field of interest that cites the most current finding in the subject area. A minimum of two to three citations to the literature per paragraph is advisable. The paragraphs must be a summary of unresolved issues, conflicting findings, social concerns, or educational, national, or international issues, and lead to the next section, the statement of the problem. The problem is the gap in the knowledge. The focus of the Background of the Problem is where a gap in the knowledge is found in the current body of empirical (research) literature.

Statement of the Problem

Arising from the background statement is this statement of the exact gap in the knowledge discussed in previous paragraphs that reviewed the most current literature found. A gap in the knowledge is the entire reason for the study, so state it specifically and exactly.

Use the words “gap in the knowledge.” The problem statement will contain a definition of the general need for the study, and the specific problem that will be addressed.

Purpose of the Study

The Purpose of the Study is a statement contained within one or two paragraphs that identifies the research design, such as qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods, ethnographic, or another design. The research variables, if a quantitative study, are identified, for instance, independent, dependent, comparisons, relationships, or other variables. The population that will be used is identified, whether it will be randomly or purposively chosen, and the location of the study is summarized. Most of these factors will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

Significance of the Study

The significance is a statement of why it is important to determine the answer to the gap in the knowledge, and is related to improving the human condition. The contribution to the body of knowledge is described, and summarizes who will be able to use the knowledge to make better decisions, improve policy, advance science, or other uses of the new information. The “new” data is the information used to fill the gap in the knowledge.

Primary Research Questions

The primary research question is the basis for data collection and arises from the Purpose of the Study. There may be one, or there may be several. When the research is finished, the contribution to the knowledge will be the answer to these questions. Do not confuse the primary research questions with interview questions in a qualitative study, or survey questions in a quantitative study. The research questions in a qualitative study are followed by both a null and an alternate hypothesis.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction for an observed phenomenon, namely, the gap in the knowledge. Each research question will have both a null and an alternative hypothesis in a quantitative study. Qualitative studies do not have hypotheses. The two hypotheses should follow the research question upon which they are based. Hypotheses are testable predictions to the gap in the knowledge. In a qualitative study the hypotheses are replaced with the primary research questions.

In Chapter 1 this is a summary of the methodology and contains a brief outline of three things: (a) the participants in a qualitative study or thesubjects of a quantitative study (human participants are referred tyo as participants, non-human subjects are referred to as subjects), (b) the instrumentation used to collect data, and (c) the procedure that will be followed. All of these elements will be reported in detail in Chapter 3. In a quantitative study, the instrumentation will be validated in Chapter 3 in detail. In a qualitative study, if it is a researcher-created questionnaire, validating the correctness of the interview protocol is usually accomplished with a pilot study. For either a quantitative or a qualitative study, using an already validated survey instrument is easier to defend and does not require a pilot study; however, Chapter 3 must contain a careful review of the instrument and how it was validated by the creator.

In a qualitative study, which usually involves interviews, the instrumentation is an interview protocol – a pre-determined set of questions that every participant is asked that are based on the primary research questions. A qualitative interview should contain no less than 10 open-ended questions and take no less than 1 hour to administer to qualify as “robust” research.

In the humanities, a demographic survey should be circulated with most quantitative and qualitative studies to establish the parameters of the participant pool. Demographic surveys are nearly identical in most dissertations. In the sciences, a demographic survey is rarely needed.

The theoretical framework is the foundational theory that is used to provide a perspective upon which the study is based. There are hundreds of theories in the literature. For instance, if a study in the social sciences is about stress that may be causing teachers to quit, Apple’s Intensification Theory could be cited as the theory was that stress is cumulative and the result of continuing overlapping, progressively stringent responsibilities for teachers that eventually leads to the desire to quit. In the sciences, research about new species that may have evolved from older, extinct species would be based on the theory of evolution pioneered by Darwin.

Some departments put the theoretical framework explanation in Chapter 1; some put it in Chapter 2.

Assumptions, Limitations, and Scope (Delimitations)

Assumptions are self-evident truths. In a qualitative study, it may be assumed that participants be highly qualified in the study is about administrators. It can be assumed that participants will answer truthfully and accurately to the interview questions based on their personal experience, and that participants will respond honestly and to the best of their individual abilities.

Limitations of a study are those things over which the research has no control. Evident limitations are potential weaknesses of a study. Researcher biases and perceptual misrepresentations are potential limitations in a qualitative study; in a quantitative study, a limitation may be the capability of an instrument to accurately record data.

Scope is the extent of the study and contains measurements. In a qualitative study this would include the number of participants, the geographical location, and other pertinent numerical data. In a quantitative study the size of the elements of the experiment are cited. The generalizability of the study may be cited. The word generalizability, which is not in the Word 2007 dictionary, means the extent to which the data are applicable in places other than where the study took place, or under what conditions the study took place.

Delimitations are limitations on the research design imposed deliberately by the researcher. Delimitations in a social sciences study would be such things as the specific school district where a study took place, or in a scientific study, the number of repetitions.

Definition of Terms

The definition of terms is written for knowledgeable peers, not people from other disciplines As such, it is not the place to fill pages with definitions that knowledgeable peers would know at a glance. Instead, define terms that may have more than one meaning among knowledgeable peers.

Summarize the content of Chapter 1 and preview of content of Chapter 2.

Source: Barbara von Diether, EdD

If you are about to embark on the task of developing a Master’s thesis in Computer Science, then this document may be of interest to you. The scope of this document is very narrow and deals only with certain features of thesis development that are unique to the field of Computer Science. For more general information, you should consult sources such as Strunk and White’s Elements of Style [3 ], Turabian’s Student’s Guide for Writing College Papers [4 ], and the University’s guide to thesis preparation.

Before we get into the heart of the matter, you should ask yourself if you have the background and skills required to successfully complete a thesis in Computer Science. The next section lists some of the skills you will be expected to possess.

While there are no hard and fast rules that guarantee you have the background and skills required to complete a thesis in Computer Science, there are some indicators. Here is a list of some of these indicators.

- A good grade point average. This indicates that you have basic academic skills. It is difficult to specify an exact cut-off, but a 3.2 on a 4.0 scale is a reasonable minimum.

- The ability to write in the English language. Practice writing. Effective communication is essential in all disciplines. If you need help, contact the Language Institute or English Department.

- The ability to express yourself orally. You will be asked to present lectures on your work at the Computer Science seminar.

- Mastery of the computer language in which you will develop your program. You should not look at your thesis work as an opportunity to learn how to program. You should be very familiar with the operating system you will use and system utilities such as editors, document formatters, debuggers, etc.

- The ability to work with others. You must be able to work with your thesis advisor, and you may need to work with other faculty and students as well.

- The ability to take direction. Your thesis advisor will give you guidance, but you must do the work.

- The ability to conduct literature surveys. You must insure that your work is current and relevant even though it may not be original or unique.

- The ability to integrate ideas from various areas. This is key to a thesis. Extracting items of interest from many sources and generating new information by integrating these items in new ways is the essence of writing a thesis.

- The ability to think independently. Your work must be your own. Your advisor will not tell you what to do at every step, but will only suggest a direction. The rest is up to you.

- The ability to perform when imprecise goals are set for you, that is, you must be self-directed.

Most theses in Computer Science consist of two distinct parts: (1) writing a significant program, and (2) writing a paper that describes your program and why you wrote it. The intent of this document is to guide you in how to do these two things. Of course, you will need to have taken certain courses, read certain books and journal articles, and otherwise perform some basic research before you begin writing your program or thesis. If your thesis does not involve writing a program, you can skip section 3.

Presumably you have a thesis topic, and it is time to start developing a program that will implement or demonstrate your ideas about this topic. You have learned how to write programs in previous courses, but usually the program you will write for your thesis is more involved than other programs you have written. Thus, it is important to use good software engineering techniques.

The requirements document explains what your program is to do. Often the requirements will be quite vague. For example, “the system must be fast,” or “the system must be user-friendly.” You’ll want to write a set of requirements that can serve as a contract specifying what is expected of your program. What’s in a requirements document? Abstractly, the answer is very simple: a statement of valid input to the program and a statement of the corresponding output. Your software will operate on some data and derive computed data. The requirements document will clearly state what the input data and output data will be. The requirements document tells what your program will do from the user’s perspective.

The specification document explains what the requirements are, but more precisely than the requirements document itself. It restates the requirements from the point of view of the developer. The specifications are explicitly and precisely stated. They are statements that you can design to and test for. Essentially, the specifications define a function from the set of all possible data input to the data output by your program.

The preliminary design document explains how you are going to fulfill the specifications. It is written before you write the program and should include a list of algorithms you will use, major data structures, a list of major functions, their inter-relationships, and the steps you will use to develop your program. Stepwise refinement and information hiding concepts should be used in developing the program, producing a detailed design document.

Write The Comments First

Understanding where and how to comment your code is important. Comments help you understand what is to be done. It is backwards to the write code and then try to explain what it does. Basic rules include giving pre- and post-conditions for selection and iteration statements, as well as blocks of sequential code. Additionally, loop invariants need to be developed for iteration statements. Data structures and their use also need to be explained.

Additional documents are sometimes required for a program. These include a user’s manual, a maintenance manual, and a test suite. Often these will appear as appendices in your thesis. The user’s manual describes the user interface to your program. The maintenance manual describes how to change, augment, or port your program. The test suite offers some validation that your program will compute what was intended by describing test procedures and sample test inputs.

Most likely others will use your program. Writing a good user’s manual will facilitate the use of your program. The important thing is to write for the naive user. It is best to assume that users of your program will know nothing about computers or their interfaces. A clear, concise, step-by-step description of how one uses your program can be of great value not only to others, but to you as well. You can identify awkward or misleading commands, and by correcting these, develop a much more usable product. Start from your requirements document to remind yourself what your program does.

If your work has lasting benefit, someone will want to extend the functionality of your code. A well thought-out maintenance manual can assist in explaining your code. The maintenance manual grows from your specification, preliminary design, and detailed design documents. The manual shows how your program is decomposed into modules, specifies the interfaces between modules, and lists the major data structures and control structures. It should also specify the effective scope of changes to your code.

How will you guarantee that your program meets its specifications? Formal verification is one “proof” technique, but it can be difficult to apply for large programs. You should be familiar with verification techniques and use them as you develop your code, but others are still going to want to see that your code gives expected results on a sample of test cases. Thus, you should develop a test suite that can be used to show your program works correctly under a variety of conditions by specifying testing procedures to be used and a variety of test cases to “exercise” the components of your program.

I believe in literate programming. that is, a program should be written to be read and understood by any person experienced in programming. The most basic method of facilitating human consumption of your program is to write good internal comments as discussed in § 3.3. Much more sophisticated methods exist; one of these is the WEB system developed by Don Knuth [1 ]. The original WEB system was written for Pascal, but WEB systems for other languages have been written, and there is even a program called spiderweb that can be used to generate a WEB system for any programming language [2 ,5 ].

Briefly, the benefits of using a WEB system are that it enables you to (1) develop your program logically, without the constraints imposed by the compiler, (2) provide for excellent program documentation and modularity, and (3) track variables and modules automatically. An index of variables and modules is produced containing pointers to where the variables and modules are defined and used. To learn more about such systems, you should refer to the cited literature.

Your thesis paper documents your work and can serve as a basis for a publishable paper. The most common mistake made by thesis students is to assume that the thesis itself will be easy to write. Consequently, they postpone writing until they have completed their programming. By the time they produce an acceptable copy, they find that a term or two of school has slipped by and they still have not graduated. Important advice is to start writing early and ask your thesis advisor for feedback on your writing. Equally important, do not plagiarize. Plagiarism can result in expulsion from school. You are expected to write your own paper, not copy from what someone else has written. It is okay to use other people’s ideas, even their own words, but you must clearly reference their work. Your paper should describe what you did and why you did it.

Everyone makes spelling mistakes, but with spelling checker programs available this type of error should be eliminated. Always run your written work through a spelling checker before you ask someone else to read it. Also, you should find someone who can correct grammatical mistakes in your paper. If necessary, hire someone from the English Department or Language Institute to correct your work before you give it to your advisor.

Also, use a professional document preparation system, for example, L A TE X. troff. or WordPerfect, which allows you to print your document on a laser printer. There is an F.I.T. thesis style file that has been developed for L A TE X. which will produce correct margins and other formats, plus automatically handle many details in the preparation of your thesis.

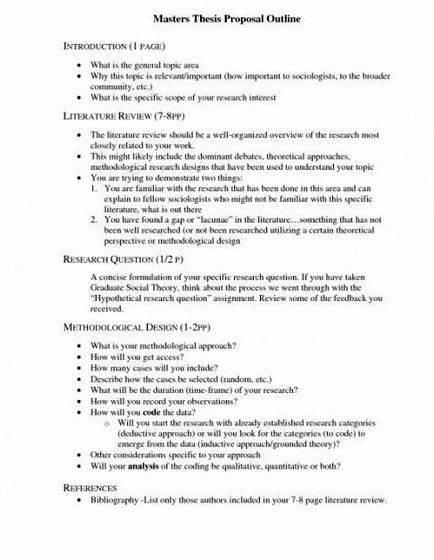

You will begin writing your paper the first quarter you are enrolled for thesis credit. You will write a thesis proposal that evolves into your thesis. Writing a good proposal is an important first step to success. Proposals will differ, but there are certain things that can be expected to be found in every one. There needs to a statement of (1) the problem to be studied, (2) previous work on the problem, (3) the software requirements, (4) the goals of the study, (5) an outline of the proposed work with a set of milestones, and (6) a bibliography.

The top-down approach, which is recommended for program development, carries over to the development of your thesis paper. Here, you should begin with an outline of each chapter. Although it is difficult to specify what should be included in each chapter of a thesis, the following outline is fairly general.

Your finished thesis must include a title page, signature page, abstract, and bibliography. See the University guide to thesis preparation for details. Make sure you follow the margin and format requirements exactly.

You should be proud of your work and want others to know about it. One way to show that you have done quality work is to publish it in a journal or present it at a conference. Thus, you should write a short 5-10 page paper that concisely explains what you did and why it is new or important. This paper can then be submitted to appropriate conferences and journals. The research you have done should provide you with a list of conferences and journals to which you can submit your work.

Below is a quick list of the guidelines that have been discussed in this document.

- How to write your program. 1. Write a requirements document that states the requirements your program must meet. 2. Write specification, preliminary design, and detailed design documents that precisely define what the requirements are and how your program will meet the requirements. 3. Write the comments first. 4. Build a scaffold, which can be removed, that supports the construction of your program. 5. Write a user’s guide, maintenance manual, and test suite. 6. Use a program document formatter such as WEB.

- How to write your paper. 1. Enroll in XE 4022 Thesis Preparation. 2. Start writing early. 3. Do not plagiarize! 4. Write a proposal that includes a statement of the problem under study, the software requirements, an indication of how the problem will be solved, and a survey of related literature. 5. Use a spelling checker. 6. Have someone proofread your paper for grammatical errors. 7. Use a document formatter such as L A TE X. troff. or WordPerfect. 8. Develop an outline for each chapter before you write it. 9. Write a short summary paper you can publish.

There are several local requirements that you should be aware of so that you do not have unnecessary problems in completing your thesis. Many of these procedures or policies are described in other documents and will simply be summarized here.

- A thesis proposal must be written and approved in the first term you enroll for thesis credit.

- A thesis committee consisting of at least three faculty members, two in Computer Science and one in an outside department, must be selected during your second thesis term.

- Once enrolled for thesis credit, you must remain enrolled for thesis credit continuously until you complete your defense.

- You must present an overview of your thesis at a Computer Science Seminar prior to your defense.

- You must have your thesis approved by all committee members at least two weeks prior to your defense.

- You must verify to the Computer Science Department Chair that all committee members have agreed that you are prepared to defend your thesis.

- Two weeks prior to your defense, you must file an announcement of the defense with the Graduate School.

- If you successfully defend your thesis and complete all work on it within the first two weeks of a term, you are not required to register for that term.

If you simply follow the suggestions outlined and discussed in this paper, you will be well on your way to successfully completing the thesis requirements for attainment of a Master’s Degree in Computer Science at the Florida Institute of Technology. Good luck!

1 D. E. KNUTH. Literate programming. The Computer Journal, 27 (1984), pp. 97-111.

2 N. RAMSEY. A spider’s user’s guide. tech. rep. Princeton University, 1989.

4 K. L. TURABIAN. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. The University of Chicago Press, 4th ed. 1973.

5 C. J. V. WYK AND N. RAMSEY. Literate programming — weaving a language-independent web . Communications of the ACM, 32 (1989), pp. 1051-1055.

Florida Institute of Technology

Department of Computer Sciences

150 West University Boulevard,

Melbourne, FL 32901-6988

Tel. (321) 674-8763, Fax (321) 674-7046,

E-mail: www@cs.fit.edu

2001 Florida Tech. this server is currently maintained by the Department of Computer Sciences. Please send your questions, comments and suggestions to www@cs.fit.edu.

William D. Shoaff

2001-08-21

Hot melt extrusion thesis proposal

Hot melt extrusion thesis proposal Writing a thesis for middle school

Writing a thesis for middle school Superconducting fault current limiter thesis writing

Superconducting fault current limiter thesis writing Writing the intro paragraph with thesis

Writing the intro paragraph with thesis Media studies phd thesis writing

Media studies phd thesis writing