Saturday, July 9, 2011

Recently, a fellow graduate student defended his master’s thesis. He set the record for the shortest time to degree in our College with a nice job lined up afterwards. But that also meant he never presented his work at a conference, or a department/college seminar. This was his first- and most important “big talk”. What follows are the top 10 tips I gave him at one point or another as he was preparing that should be a help to anyone getting ready for a “big talk”.

1) Know Your Audience

Everyone will tell you to know your audience, which couldn’t be truer when you’re planning the introduction to your talk. Sure, there is a big difference between talking to high school students and presenting at a conference, but try to think: who is coming to my talk? If they are all cellular biologists like you, then skip the central dogma slide. But if you have a mix of disciplines you need to be able to explain your work to a biologist, as well as an electrical engineer. Imagine you’re giving the talk to one person with each potential background. Would each person be able to follow it? Sometimes you need to sacrifice some specific details in order to explain the important stuff to everybody. (But you should be able to talk extemporaneously on the specifics if anyone asks!)

2) Justify Yourself

An introduction is more than just a history of your field up until now. That is, it’s more than a literature review. You need to review the current literature, but more importantly put your research into context. What have you done (or what are you doing) that no one else has done? Keep in mind that just because no one else has done X doesn’t mean doing X is worthwhile- there might be a very good reason why no one else has done it!

As you introduce your research you’ll likely explain why you’re doing it, but make sure you also explain why others in the field care. Even more important that justifying your work is justifying your conclusions. You MUST be able to back up any claims with solid references, or solid experimental results! In many cases this means statistical tests of quantitative data. When in doubt, err on the side of “inconclusive” or qualify/temper any of your statements rather than stretch your conclusions.

3) Tell A Story

One of the most jarring moments in a bad presentation is the lack of transitions. Your presentation should flow from slide to slide and section to section. This will most likely mean that you aren’t going to present your experiments in the order that you did them. You’re NOT telling the story of you working in the lab! Think: what are the overall conclusions from your work and how can you explain and prove the things you’ve concluded? Walk your audience through the story, laying out the evidence convincing them you’re right about your conclusions. One last thing: you’ve (hopefully) done a lot of experiments, you’ve invested a lot of time, energy, and maybe even money into these experiments and you want to show off everything you’ve done. But if an experiment or data slide doesn’t fit in the “story” you might have to leave it out. If you can’t make it fit in the flow of your story and/or you don’t NEED it: leave it out.

4) Sweat the Small Stuff

The little details are important. Even if you have some really great results to show, you’re going to anger, upset, or at least annoy your audience if you don’t pay attention to details. Some examples:

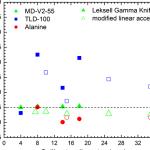

- Label the axes of any graphs (with units), don’t use 10E3 mV (when V works) and don’t forget error bars!

- Make sure any images have scale bars, and label items of interest. (You might know what’s a cell and what’s dust, but everyone else might not!) Use the same size, color, and font text.Try to use the same slide layout.

- Make all your graphs, diagrams, molecular depictions, etc. with the same program throughout. It’s noticeable if you copied one molecule from a paper, made some in ChemDraw, and others with ChemSketch. The same holds true with graphs in Excel versus Origin.

- Excel can be your friend but if you use the default graph settings it will be your downfall. Don’t leave on the gridlines or use the standard random colors. Oh, and look into Origin.

5) Present in Bite Sized Slides

For each slide be sure to explain everything. Explain the x and y axes of your graph, explain what a large value indicates, and a low value indicates. Walk people through how you set up the experiment, how you collected the data, analyzed the results, and talk about the controls. Before moving to the next slide, restate the major finding or “take-away” from this slide. What did this experiment tell you, and what questions are still unanswered. This will help build in transitions as you tell your story. You probably know every piece of your presentation inside and out, but you need to remind your audience of salient points from earlier in the presentation.

Giving the Presentation

6) Practice, Practice, Practice!

Even the most beautiful slides with the most logical flow and greatest data can trip you up if you don’t know what you’re going to say. It should go without saying that you can’t just read off of your slides, but seriously: practice, practice, practice! Run through it in your head, do in out loud and most importantly, do it in front of other people: schedule practice talks! In the days leading up to your presentation you should be able to run through the talk in your head without notes. As you’re walking the halls, driving, or cooking you should run through the talk over and over. The goal is that when you get up there on the big day, everything comes out naturally- almost second nature. For me, I need to write a script- I don’t memorize it word for word, but the act of writing what I want to say helps. Of course, if you’re a naturally gifted speaker and can give a talk on the fly you’re set- but you should still practice!

7) Don’t wait until the last minute

The goal of practice talks is to get feedback from friends, lab mates, classmates in general, and hopefully your advisor. It does you little to no good if your practice talks are the day or two right before your talk. You need to give yourself time to integrate their changes into your presentation- both the slides and the talk. I like a formal practice talk the week, and two weeks before the talk. This gives you enough time to change slides, change what you might say, and change the written document (if applicable). If you give yourself enough time you might even be able to squeeze in an extra experiment before the big day to fill any “holes” in your story.

8) Try out the room and equipment

Not all practice talks are created equal. Sure, you can run through the slides on your laptop in your advisor’s office but you really need to get up in front a group of people- preferably in the same room you’ll be giving your presentation. Not only do you get in the presentation mind set, but you get used to the space, you test the equipment and therefore minimize surprises on presentation day. For example, one talk I went to recently was marred by the screen flashing horizontal bars randomly- it was nearly seizure inducing. Finally, they borrowed someone else laptop but do you really want that stress on your big day? Dress rehearsals are your friend!

9) Be comfortable with your knowledge

In many cases when you present your research you will be the most knowledgeable person in the room about your topic. Be comfortable with that, and confident that you know what you’re talking about. Professors and especially your thesis committee (whom probably know a decent amount about your topic) can smell fear like sharks find blood in the water. Don’t make it easier for them! Don’t let them know you’re nervous, or might not be sure about something. Confidence goes a long way, BUT don’t let it go too far. Don’t get cocky because nothing is more tantalizing that crushing an OVER confident student. Be confident, but not cocky.

10) Be humble

You know your research, your techniques, your experiments, and your data. But you might get questions a little removed (or a lot removed) from your research. You might even get questions you don’t know the answer to, or aren’t sure about. The best advice I can give someone going into a defense- even last minute- is don’t be afraid to say “I don’t know.” Guessing, or even worse, making something up, is so much worse that admitting you don’t know the answer to a question. I’ve seen professors who will grill a student and not stop until they say “I don’t know” or they catch them answering wrong (guessing/making something up). You’ll never know everything about everything so don’t be afraid to say “I don’t know”. But it is inexcusable to guess or make up an answer- it will only get more painful from that point on. On the flip side, don’t answer every question with “I don’t know”- it’s not a get out of jail free card!

Do you have any other words of wisdom for students getting ready to defend? Let’s hear them in the comments!

Guest blogger Nick Fahrenkopf is a Ph.D. candidate studying nanobiosciences- applying physics and engineering concepts and techniques to biological and medical problems. Outside of his research he enjoys curling, and resists the urge to dig too far into the science behind it. He likes doing scientific outreach in the community and blogging For Love Of Sciences. Follow him on Twitter @FLOSciences .

This post has been viewed: 233546 time(s)

One more hint: when you practice, practice standing up. You might feel like a dork standing up in your living room, but it feels very different and you need to get used to it!

Also, do not put more than the bare minimum on your slide, least of all text which you are going to say anyway! Your slides are not supposed to tell a story on their own, they are only supposed to support your story with visuals *WHERE NECESSARY*. Good luck!

Dr. Girlfriend

I’ll add a couple more.

* Recognition is important and the generic “we” is not appropriate for a defence seminar – your committee want to know what YOU contributed to the project. Do say “I did this” and “I thought that..”. but where appropriate say “a former postdoc, [name], did this” or “a fellow grad student, [name], suggested I try..”. Of course should try and show data you generated yourself, but sometimes it is necessary to the story to display data collected by others in the group and naming names shows you respect your colleagues.

* Guessing an answer is good, providing it is an educated/informed guess and you use the disclaimer “I don’t know, but I would guess XYZ because. ”

* Laser pointers need to be handled with care. I have a horrid habit of get overexcited and over using them. A wooden pointer helps folk like me because it is so cumbersome that I only use it when pointing is really necessary!

* A student support group can offer many benefits, one being an audience to practice talks on and get critical feedback from. However, it has to be give and take to work.

I love #9. And I have a difficult time stressing to people that they’re most likely an, if not the, expert, when giving a presentation.

11. Your committee does not want you to fail. If they have any wit at all, they wouldn't let you anywhere near a defense unless they thought you were ready for it. When someone fails a thesis defense, something has gone very badly wrong.

This does not mean they won't make you sweat, squirm, or feel uncomfortable. They will. But when committees put the pressure on, it's by and large to make sure that the science is solid.

12. Bring food for your committee. People who are fed tend to view things in a much more favourable light:

Alchemystress

Great advice. I hate when people don’t have scale bars. I work a lot on nano type things and my main complaint with biologists talks is they will image under electron microscope talk that something is big or small and then show image without scale bar ahhh then i spend time trying to figure out what big or small is to them. whew ok out of my system

Also my former boss gave me great advice. practice your talk and memorize the slides you have in order and what is on them and what you cover with them so you don’t look at the slides on screen or are surprised by a slide. or as it always happens (and this happened to me) the powerpoint computer freezes or something and slides are gone be able to do your talk without them.

anything one should stay away from Dr. Z? Because I could get carried away with that. I’d imagine most fish is off the table. Maybe something that could braise or cook while I do touchup, like a cassoulet or braised pork shoulder, some shcarole and gnocchi?

JaySeeDub: Yeah, that’s putting way more thought than into it than I’ve seen. Cookies and maybe some drinks is more typical speed around here. Sometimes a little more.

P.S.-Not “Dr. Z” – that nickname is taken by one of my co-workers in my department.

Your first one is huge- you need to be clear what YOU did, and you need to acknowledge appropriately. The other ones are spot on too!

I’ll add a couple more.

* Recognition is important and the generic “we” is not appropriate for a defence seminar – your committee want to know what YOU contributed to the project. Do say “I did this” and “I thought that..”. but where appropriate say “a former postdoc, [name], did this” or “a fellow grad student, [name], suggested I try..”. Of course should try and show data you generated yourself, but sometimes it is necessary to the story to display data collected by others in the group and naming names shows you respect your colleagues.

* Guessing an answer is good, providing it is an educated/informed guess and you use the disclaimer “I don’t know, but I would guess XYZ because. ”

* Laser pointers need to be handled with care. I have a horrid habit of get overexcited and over using them. A wooden pointer helps folk like me because it is so cumbersome that I only use it when pointing is really necessary!

* A student support group can offer many benefits, one being an audience to practice talks on and get critical feedback from. However, it has to be give and take to work.

Good points too! I reminded myself that no one I knew had ever failed their oral exam. So do you best, take whatever verbal beating they give you with grace, and you'll be fine. Don't wrack yourself with nerves!

Oh, and not only food, but coffee. If you don't bring coffee- or bring bad coffee- you'll fail. OK, maybe not fail, but it will not be pretty.

11. Your committee does not want you to fail. If they have any wit at all, they wouldn't let you anywhere near a defense unless they thought you were ready for it. When someone fails a thesis defense, something has gone very badly wrong.

This does not mean they won't make you sweat, squirm, or feel uncomfortable. They will. But when committees put the pressure on, it's by and large to make sure that the science is solid.

12. Bring food for your committee. People who are fed tend to view things in a much more favourable light:

My two bits of advice:

1. Show up ahead of time. Lets you get more comfortable with your audience before things begin, and adjust to last minute problem – in the room I was in, for example, the video cable for a laptop does not reach the podium, so the whole layout of the room – and some of the style of the presentation, had to change.

2. Don’t panic. If a faculty member asks you a question, odds are its not because they want you to go down in flames. If the answer is “I don’t know”, or “We didn’t look at that” – say so. Noone expects a masters paper to be a magnum opus.

OmicsScience

great tips and great comments.

Especially tips 9 and 10.

You should think it is a scientific discussion between the expert in the field (i.e. you) and experienced researchers (the committee). So the answer ‘I don’t know’ is always acceptable in such a discussion. Of course, if you have an idea or speculation it is good to mention it; this way you prove that you are able to think, but if you are not sure, you must say it.

Last, show your enthusiasm.

JaniceF

I personally value speakers who can tell me what their biological question is and/or hypotheses based on previous literature/data, but provide expectations for their work. You start off with a context but by talking specifically about how your question(s) fill a gap and what they are, narrows the focus.

Repeat the question back to the committee to make sure that you’ve really understood what they are asking. And take time to answer the question.

Standard page layout for thesis proposal

Standard page layout for thesis proposal Le diable amoureux cazotte dissertation proposal

Le diable amoureux cazotte dissertation proposal Subhash khot phd thesis proposal

Subhash khot phd thesis proposal Mg university kottayam online thesis proposal

Mg university kottayam online thesis proposal Saikat saha phd thesis proposal

Saikat saha phd thesis proposal