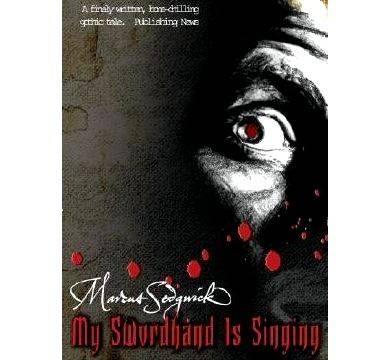

The forests of Eastern Europe are not just the home of vampire lore, but of a wealth of other superb myths. First and foremost among these for me were the stories about the Shadow Queen, as recorded in Sir James Fraser’s still unsurpassed work on folklore, The Golden Bough. Fraser recounts how the Shadow Queen is a manifestation of an archetypal figure from myth, with accompanying rituals. The Queen, representing the evils and dangers that pervade the winter for the primitive mind, is ritually worshipped in the form of a straw dummy dressed in a villager’s clothes, and then sacrificed in a Spring fire festival, thus banishing her malign influences for another year.

Or at least it is hoped so.

In My Swordhand is Singing, I conflated stories of the Shadow Queen with a less concrete legend, that of the Winter King, a figure for good. I wanted to show how myths can often be supposed to arise from real incidents and this is the case with the Winter King; stories that I based on accounts of how the dangers and perils of the forest in Winter have saved the peoples of eastern Europe from attack, as was the case with the Turkish invasions in the middle ages. Here, the forest itself seemed to be a player in the history, as the last stragglers of the invading Turkish forces were last seen lost deep amongst the trees, where, we can only guess, the Winter King saw an end to them.

Most people are familiar with the whys and wherefores of the vampire, but few realise how far a journey this nightmare figure has made. Today, we can recognise a vampire in film or book by pointed canine teeth, a cape maybe, or an accompanying bat.

The suave, sometimes overtly attractive vampire of modern myth is very far from the original revenants of the folklore where these creatures originated. In fact, those first vampires are more like zombies with a bloodlust being either horrific bloated corpses returned from the earth, or indistinguishable from their former living selves (and what a dangerous thing that would be). Sometimes even the bloodlust is absent; one vampire’s preferred sustenance was noted to be milk! In many instances it is impossible to distinguish between what we would know as the werewolf and the vampire.

In writing this book I sought to capture the flavour of the early reports of vampirism, from the well known case of the Shoemaker of Silesia in 1591, to the unnatural dealings of Peter Plogojowitz in 1725, via a myriad of less popular stories collected from various eastern European countries: Pëtr Bogatyrëv’s studies of the sub-Carpathian Rus and Alan Dundes’ unsurpassed anthropological collection; The Vampire: A Casebook repaid their reading many times over. I also urge you, if interested, to read Paul Barber’s Vampires, Burial and Death which expounds a well-argued theory using forensic pathology on the possible bio-chemical origin of many of the traits of the vampire.

To make a coherent story I had to pick and choose from among hundreds of stories, many of which flatly contradicted each other for there are almost as many types of vampire as there are vampire stories.

One example would be the vampire’s reaction to light in some stories they may only appear at night, in others they are immune to any potentially destructive power of this force for good. Even giving vampires a name is not a simple thing: here are just a few of them; krvoijac, vukodlak, wilkolak, varcolac, vurvolak, kiderc nadaly, liougat, kulkutha, moroii, strigoii, murony, streghoi, vrykolakoi, upir, dschuma, velku dlaka, nachzehrer, zaloznye, nosferatu this last, quite familiar to us, is the vampire’s name in that most unholy of vampire lands Transylvania, literally the ‘Land beyond the Forest.’ Transylvania is in fact a beautiful place, with mountains, pastures and forest just as described in the book. And it is here that the stories of the Miorita, the Wedding of the Dead, and the Shadow Queen would be familiar to local people, though again I have had to take certain liberties for the sake of the story. Nowadays we know all these fabulous stories of the undead to be myth, though it might be wise to remember that there are still some people who do not agree with this conclusion. Even in the first few years of this new century stories have emerged from Romania of modern day belief in vampires; in 2004 the relatives of a Romanian man were prosecuted for exhuming his corpse, burning his heart and drinking the ashes in water, because they believed he had been visiting them in the night

Deep in the woods of Romania, strange rituals can arise, and surely none more so that the Wedding of the Dead, a genuine ceremony that is performed when a young man dies before he is married, and a young unmarried woman from the village consents to marry him at his graveside. The accounts of such marriages are as touching as they are chilling.

Finally, I must also mention the Miorita (pronounced Mio-ritsa), a folk ballad from Romania that tells the story of a beautiful young shepherd and his grisly murder at the hands of two supposed comrades. The exact meaning of the song is disputed in academic circles; I chose one meaning and used it as suited my story; others would disagree with the conclusion that the message of the song is to teach us to be ready to accept death, in order that we may live free from fear of it, but this seems the most apt and poetic interpretation.

Writing a mystery novel plot ideas

Writing a mystery novel plot ideas Writing a mystery thriller novels

Writing a mystery thriller novels Customer letter writing bad checks

Customer letter writing bad checks Phd writing problems in elementary

Phd writing problems in elementary Murder mystery character profiles writing

Murder mystery character profiles writing